The Grapevine Art & Soul Salon

Entertaining Ideas: Barbara Knott

Recovering a Lost World

A New/Old Vision of What It Means To Be Human

runs through the world and dances in rhythmic measures.

It is the same life that shoots in joy through the dust of the earth

in numberless blades of grass and breaks into tumultuous waves

of leaves and flowers.

It is the same life that is rocked in the ocean-cradle of birth and of death,

in ebb and in flow.

I feel my limbs are made glorious by the touch of this world of life.

And my pride is from the life-throb of ages dancing in my blood

this moment.

This song/poem was published in 1912 by Rabindranath Tagore of India in a slim volume called Gitanjali (Song Offerings), for which he won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913, when we humans were stumbling into the first world war. A self-described optimist, Tagore was declaring, instead of war against his own species, quite a different perspective, clear in mind as well as heart and body, of his deeply felt kinship with all of creation, his gladness for being one among such a glorious choir of voices in the largely untamed forces of nature. He was expressing again and anew the pantheistic/animistic view held by the English romantic poets and by the world's indigenous peoples who, when they survived an invasion, were usually pushed onto reservations, from which some eventually made their way into the mainstream of colonized nations and others chose to keep their cultural identity.

What we know of indigenous people teaches us that they have, even now, managed to maintain oral traditions that proclaim a humble human place in a vast more-than-human community. They are perhaps the lucky ones in that they have held on to important values, including a reverence for nature and a practice of always giving back something for what has been taken. These are values that badly need to be seen and felt by those of us in the larger societies that surround them. A reciprocity of gifting, a practice known well among indigenous people everywhere, may be the only way a world in which life feeds on life can sustain itself.

Something of this reciprocity can be found in D. H. Lawrence's "Pan in America," one of the posthumous papers published in Phoenix (New York: Viking Press, 1936, 24-7).

In this passage, Lawrence poses the question and identifies the problem:

What can a man do with his life but live it? And what does life consist in, save a vivid relatedness between the man and the living universe that surrounds him? Yet man insulates himself more and more into mechanism, and repudiates everything but the machine and the contrivance of which he himself is master, god in the machine.

For the solution, he articulates a vision of what it means to be human and fully alive:

Here, on this little ranch under the Rocky Mountains, a big pine tree rises like a guardian spirit in front of the cabin where we live. ... The tree has its own aura of life. ... It is a great tree, under which the house is built. ... The tree gathers up earth-power from the dark bowels of the earth, and a roaming sky-glitter from above. ... It vibrates its presence into my soul. ... I have become conscious of the tree, and of its interpenetration into my life. ... I am conscious that it helps to change me, vitally. ...

Of course, if I like to cut myself off, and say it is all bunk, a tree is merely so much lumber not yet sawn, then in a great measure I shall be cut off. So much depends on one's attitude. One can shut many, many doors of receptivity in oneself; or one can open many doors that are shut.

I prefer to open my doors to the coming of the tree. Its raw earth-power and its raw sky-power, its resinous erectness and resistance, its sharpness of hissing needles and relentlessness of roots, all that goes to the primitive savageness of a pine tree, goes also to the strength of man.

Give me of your power, then, oh tree! And I will give you of mine.

He is describing the tree that Georgia O'Keeffe painted and called "The Lawrence Tree," under which he sat to compose his work just outside the cabin where he lived with Frieda during the 1920s.

That is the reciprocity we are looking for, coming from a sensibility that might keep us from further slaughter of earth's tree populations and so many animal species at risk of extinction: wolves, panthers, polar bears, rhinos and elephants, bluefin tuna, sea turtles, butterflies .... and eventually ourselves.

Just over a century after Tagore wrote "The Stream of Life," and nearly a century after D. H. Lawrence wrote "Pan in America," we are more in need than ever of a new vision, for we humans have become so out of touch with nature that we've destroyed more than we've created out of the land, far more still than we have given back. And yet we have nostalgia for the olden times and a yearning for the companionship of animals. Diane Ackerman reminds us,

Just as our ancient ancestors drew animals on cave walls and carved animals from wood and bone, we decorate our homes with animal prints and motifs, give our children stuffed animals to clutch, cartoon animals to watch, animal stories to read.

Stuffed animals as carriers of soul? The child in each of us displays a sense of kinship with all life in responding warmly to friendly animal images. But what of the real animals? Will we accept a sentimental attachment to stuffed ones as a substitute for the wildlife on our planet? We are, as a culture, generally responsive to broad appeals for contributions to wildlife funds, and the work of animal rights organizations is indispensible. In addition to that work, we need a deeper vision.

Theodore Roszak says in Ecopsychology: (2)

Even though many environmentalists act out of a passionate joy in the magnificence of wild things, few except the artists - the photographers, the filmmakers, the landscape painters, and the poets - address the public with any conviction that human beings can be trusted to behave as if they were the living planet's children.

Too often in philosophical and religious teachings we hear messages that direct our attention away from the world, the earth, the body and the presence of eros in nature. Such abstractions are spiritual. What we want is soul, a term and a reality that holds both spirit and nature, right at the place where they conjoin and contain all of creation. More often than not, the best human expression of nature ensouled is in the arts.

Bill Plotkin tells us in Soulcraft (43):

Even in our synthetic, egocentric society, the soul stirs in our subterranean depths endlessly calling, pushing up like a flower through the cracks in the concrete pavement of our lives. We catch glimpses in our dreams and in fragments of poetry and song, in the distant howl of a coyote or in a bird's sudden flight, in sunsets and the rapture of romance.

The phrase "rapture of romance" gives us a direction for change that is echoed in several places, as in David Tacey's discussion of unitive consciousness in Minding the Animal Psyche (331):

We may need to fall in love with the world ....

Hear Thich Nhat Hanh in Spiritual Ecology (303):

Real change will only happen when we fall in love with our planet.

We have D. H. Lawrence's words for this person-planet interdependence in Complete Poems (617):

The quick of the universe is the pulsating, carnal self, mysterious and palpable. So it is always.

There must be the rapid momentaneous association of things which meet and pass on the forever incalculable journey of creation: everything left in its own rapid, fluid relationship with the rest of things.

Here we may think of Whitman's "Song of Myself" as a powerful evocation of what it means to be fully alive in the world. Lawrence says, Whitman's is the best poetry of this kind. ... The clue to all his utterance lies in the sheer appreciation of the instant moment ... .

Bill Plotkin in Soulcraft (42) corroborates Lawrence:

Walt Whitman is a space the Milky Way fashioned to feel its own grandeur.

The same might be said of D. H. Lawrence, whose writing in its entirety contains this new/old vision of what it means to be human.

From East to West, from Tagore to Lawrence, we see the gradual unfolding again of a vision: humans alive, fully alive, and a part of what Lawrence called "the living incarnate cosmos." At the time they lived and wrote, the world had become so defined by Descartes' "I think, therefore I am" and by the industrial revolution and by the movement into a world war, that the two poets appear to us now as the visionaries they certainly were. That a few could emerge to say there is no "therefore" in my world (as Lawrence did) and to sing of a return to nature as Tagore did, and to say as Picasso did, "I don't develop, I am" ... these significant moments prepared the way for the work of artists who came after them and for environmentalists and ecopsychologists and spiritual ecologists mentioned throughout this and other articles in The Grapevine to do their work of recovering a lost world. The beginning and end of Maya Angelou's "When Great Trees Fall":

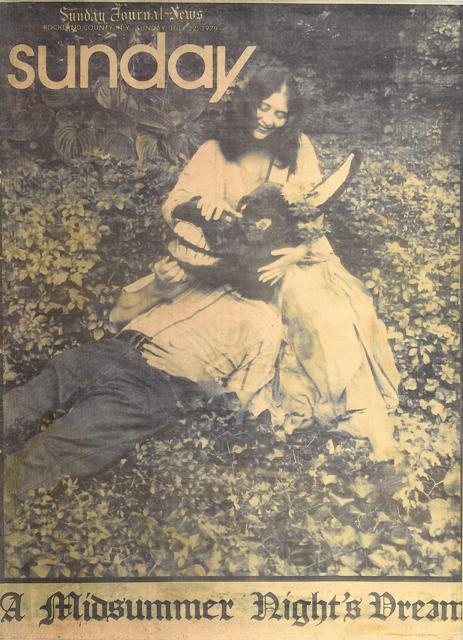

One of the great powers alive in humans is the power of imagination, which may after all be another name for soul: the builder of subtle bodies and subtle worlds out of images that come directly from nature, even when they are wildly conceived in the human mind. Shakespeare, a great soul who let us know that we can be and be better, was in love with the wild when he lived four hundred years ago and composed A Midsummer Night's Dream, a dramatic paean to his vision of human interaction with nature through imagination. In the photo below Barbara Knott is Titania, Queen of the Fairies, with Bottom the Weaver, here turned into a jackass and having the time of his life with her - in the wilderness, of course, where humans sometimes harmonize the actual and the imaginative in remarkable ways. The photo is from a mountainside production during the 1980s of A Midsummer Night's Dream in Nyack, N. Y., to raise funds for restoring the Tappan Zee Theatre where, among others, Liza Minnelli got her start. Actress Helen Hayes, who lived in Nyack at the time, was in the audience and responded warmly to our play. Note: See Views and Reviews, Recommended Reading for a full bibliography of the books quoted above, along with brief introductions.

The Tagore poem can be found online in several places by Googling. It is also listed as being in the public domain, hence our publication of the complete poem. Maya Angelou's poem appears in full online, where you can also find the Diane Ackerman quotation.

rocks on distant hills shudder,

lions hunker down

in tall grasses,

and even elephants

lumber after safety.

...

And when great souls die,

after a period peace blooms,

slowly and always

irregularly. Spaces fill

with a kind of

soothing electric vibration.

Our senses, restored, never

to be the same, whisper to us.

They existed. They existed.

We can be. Be and be

better. For they existed.

Copyright 2017, Barbara Knott. All Rights Reserved