The Grapevine Art & Soul Salon

Tracking History: Jonathan Knott, Host

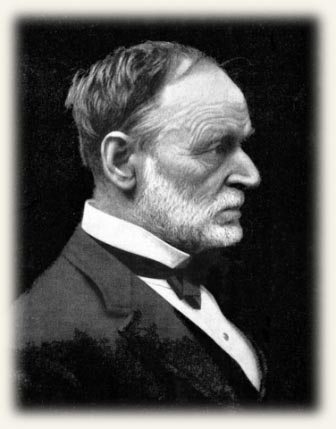

A FRESH LOOK AT GENERAL SHERMAN

September 2nd of this year marked the 150th anniversary of the fall of the city of Atlanta to Union forces in the Civil War. While this may seem like ancient news, participation in reenactments of 1864 battles this year have been at an all-time high all over the country, and perhaps no major city in America has its identity more rooted in the Civil War than our state's current capital. And perhaps no one person is more associated with its identity than the man who originally burned it to the ground: William Tecumseh Sherman.

Atlanta wasn't even the capital of Georgia when Sherman marched through—that was Milledgeville. Atlanta was only 30 years removed from a settlement being wrested from the Native Americans and turned into a railroad hub. But rail was absolutely vital in the Civil War, and Atlanta was the most vital hub in the south. Sherman wasn't content to sack the city and destroy its usefulness to the Confederate war effort, however. He had roughly 100,000 soldiers under his command, but rather than continue the bludgeoning tactics in the field that Grant employed with his superior numbers, Sherman decided to try a new tactic.

Armies at that time were cumbersome beasts that trailed long and slow supply lines to keep them fed and equipped. One advantage the Confederates had was superior cavalry, and they were able to wreak havoc by causing distractions and then sneaking around these enormous Federal armies and attacking their supply lines, often to great effect. Sherman pared his army down to 62,000 men and instructed them to march with nothing but their basic equipment and to live off the land instead, which included civilians' livestock and the houses that the his forces often looted and burned on the way.

This strategy was unheard of on a large scale in war at that time. Sherman called it "Total War" and had the troops march in this fashion (leaving only churches and hospitals standing) from Atlanta all the way to Savannah with the intention of "making Georgia howl" (in his own words). Needless to say this didn't make him very popular in the South, then or now. Most of us who live here know at least someone's grandmother who still refers to Sherman as "that damned Yankee villain" or some similar curse. Was he really such a monster, and was his whole life defined by that one event? I did a little digging and was surprised at what I found out.

Contrary to popular opinion, Sherman seems not to have hated the South. He was actually stationed for a time in the early 1840's in South Carolina, and, despite being from Ohio, was quite a figure in the upper crust of Charleston society while there. He found Charleston "so bright and delightful, that I have almost renounced all allegiance to Ohio, although it contains all whom I love and regard as friends." It takes a complex man indeed to set fire to such a place later in life.

After several years of ballroom dancing and foxhunting, the Mexican war interrupted his lifestyle. Rather than being sent to battle, however, he was sent on a seven months voyage around Cape Horn to California to serve as a quartermaster in what was at the time a far-flung frontier. Thus began a particularly fascinating and little known time of his life, as he helped shape the future of that state. He arrived in a port that would be named San Francisco only two days after he landed. The handful of soldiers that were there were among the only white people who lived in California at the time; it was the Gold Rush that helped settle the territory.

How did the Gold Rush come about? Sherman accompanied the military governor on a ride through the gold fields around San Francisco, and the latter's report to the government on their findings wound up launching the Gold Rush. Sherman didn't mine for gold himself, but set up a mercantile outfit to equip miners and made a tidy profit off it.

His involvement in the creation of the state didn't end there, though. He was appointed to survey and help design the city of Sacramento (now the capital). He became vice president of California's first railroad. He was appointed commander of the state militia. He was a banker in San Francisco before the Panic of 1857, which was several years before the Civil War started. In 1869 the citizens of California presented him with the gold badge (in the form of a bear) of the Society of California Pioneers. Quite an impressive resume, is it not? Yet who among us associates Sherman with California or even was aware he'd been there at all?

Sherman led a complex and fascinating life full of such accomplishments and strange contradictions. He finished well at West Point, though he was undisciplined. He was from Ohio, yet he loved the South. Despite all his prior military experience, he didn't want to go to war and accepted his commission grudgingly. He didn't do well in his first few battles and almost got discharged among accusations from his peers that he might be insane. Yet he gathered himself, worked well with Grant, and revolutionized modern warfare by destroying the part of the country he loved best. Equally in the spirit of contradiction, after the war he became close friends with Joseph E. Johnston, the Confederate general originally in charge of defending Atlanta (he was replaced at the last minute by John Bell Hood, who was no match for Sherman). Johnston even went to New York to attend Sherman's funeral. He caught a cold from standing in the rain to watch it, dying himself two weeks later.

The Atlanta campaign was closely monitored by Northern newspapers, and Sherman's victory helped Lincoln get reelected in 1864. Yet when he was offered the Republican nomination in 1884, Sherman said "I will not accept if nominated and I will not serve if elected." He was both loved and hated; there seems to be no middle road for this enigmatic man. And while most of the hatred comes from the people of our fair city, is it not at least a little bit thought provoking that Atlanta didn't become a great city until he gave us a reason/excuse to turn it into one? The Phoenix can only rise from ashes. If it weren't for "that damned Yankee villain," Atlanta might just be another Abeleine or Cheyenne: a footnote in the history of an archaic transportation system rather than the ninth largest city in America and the cultural epicenter of the southeastern United States.

Readers interested in learning more about Sherman, including his more unsavory qualities, can refer to sources like

General Sherman on the “March to the Sea,” 1865

and

Nine Things You May Not Know About William Tecumseh Sherman

TRACKING HISTORY ARCHIVES

Copyright 2014, Barbara Knott. All Rights Reserved.