The Grapevine Art & Soul Salon

Tracking History: Jonathan Knott, Host

While not all of us spend time wandering ancient battlefields or poring over dusty archives trying to fit pieces of the past together, history is of moderate interest to most people, even if they don't always realize it. Have you ever noticed someone pick up a 30-year-old magazine, look at the advertisements and laugh about how different people were back then? How many families are you aware of that don't have at least one person in charge of holding on to heirlooms? It's not that Great-Grandma's sewing needle or a lock of Uncle Jimmy's baby hair is worth any money or ever will be; it's that the human mind has built within it a strong desire to hold onto relics of the past, often without reasons anyone can explain.

Some people (like me) take this interest much further. When I dump the change out of my pocket after arriving home, I wonder whose hands and pockets it's been through before winding up in mine. Could that series 1985 quarter have been bounced 600 times off an Ole Miss frat house table into a glass of beer, causing promising young minds to miss the next day's test? Could one of Ronald Reagan's Secret Service bodyguards have used some of it to buy a Jolly Rancher? Both? Much more? Certainly.

It doesn't take much to start a search for something's origins, and thus use some of the 90-odd percent of the little used part of our brains to paint a bright and vibrant (or maybe dark and murky) world in which people once lived and loved, participated in the mundane, the fascinating, were bouyed by friendship and torn with grief, where a pistol might have sat on a dusty shelf for a hundred years or it might have been used in a single moment to start a war and change the course of millions of lives.

I dedicate a good part of my time to investigating such possibilities with passion; thus the creation of this column with which I will share some of my findings and musings with you.

My first entry starts with a simple spoon....

Journey to Andersonville

The wooden spoon in question belonged to a Civil War soldier, John Lynn Baldwin, 57th Indiana Volunteers, Ivan Lester’s great-great-grandfather. Ivan gave the spoon to me along with information about his father’s maternal family in Indiana. The handle is smooth and well finished as if store-bought, as is the back of the spoon itself, yet the concave part is rough and seemingly unfinished. Why it was left that way is a mystery. What makes this spoon special (besides its age), is that Mr. Baldwin was one of the unlucky Union soldiers to have been captured and held at the infamous Andersonville prison camp in south Georgia, and he apparently managed to survive and bring this relic home with him.

The spoon afforded me the perfect opportunity to honor the man’s memory and find out more about one of the sordid events in American history at the same time. I pondered the relic along with my reasons for traveling several hours each way in a military tour bus to Turin, Georgia, with officers giving the tour dressed in period uniforms and with several other majors and colonels who went along for the visit.

I have often been drawn to places where sobering things have occurred; it’s not just the rubberneck in me that needs to stare at highway accidents (although that’s part of it); it’s a way to stay grounded in the realities of human nature. In a world full of wonderful high-powered toys and gadgets that’s becoming more and more insular for individuals, I find a frequent sojourn into the past to be a personal necessity. One convenient thing about human history: it’s all around us. One does not have to travel all the way to Auschwitz to experience the horrors of a war-time prison camp, for instance, as I was demonstrating.

While most of us have seen the propaganda photographs of the starving and emaciated Andersonville prisoners made when they were liberated by Sherman in 1864, I found the camp one of those places I thought I knew a lot about (and certainly should have), but really didn’t. The camp at Andersonville (known as Camp Sumter) was designed in late 1863 to help hold the excess of Union prisoners that the facilities in Richmond couldn’t contain (Grant had just ordered that there be no more prisoner exchange between the two sides). Since the Confederates didn’t have room in the capitol city, they selected an area deep in south Georgia that was far enough out of the way of just about anything to be ideal, at least in theory. In practice, however, it was a nightmare.

They originally cleared out 16.5 acres (twice the size of my yard!) to hold 10,000 prisoners. Ten more acres were soon added, but the population swelled to 32,000 in just a few months, and the death toll averaged 100+ daily. In 14 months, almost 13,000 Union soldiers died at the camp. Food was scarce (especially later on, when the blockades tightened and the Confederates had little themselves) and the prisoners had no fresh water or shelter. Most who died did so of starvation, exposure and disease.

I won’t go into a history lesson here; it’s better to watch the 1996 movie Andersonville, as we did on the ride there, to get geared up (or down, as the case may be). It’s not for the squeamish or the easily depressed. However, the story is so fascinating it’s impossible to ignore, and viewing a major motion picture to flesh things out is an excellent idea for those unfamiliar with the background. Historical landmarks are often much less impressive in person unless you’re fairly familiar with the events that made them so. Just don’t watch The Andersonville Trial on the way back, as we did, unless you’re truly a masochist. Two and a half hours of a pot-bellied William Shatner representing the voice of American righteousness in the courtroom is, again, not for the faint of heart.

Andersonville is now made up of three main parts: a national cemetery (where soldiers are still buried), the Historic Prison Site, and the National Prisoner of War Museum, dedicated to all American POW’s. Time constraints prohibited my visiting the museum on this trip (I plan to go back later this summer), but I did do a complete tour of the campsite. It is nothing like what one would imagine. The wooden walls have mostly rotted away now (though the main gate entrance and guard towers have been authentically reconstructed), and the boundary is marked off with a double row of white stones. The inner row represents the perimeter of the camp, the outer row (only a few feet further out) represents the “kill line,” the spot where, if a prisoner stepped towards it, he would almost invariably be shot without warning.

The ground itself is a big clearing in the middle of a woody area (the first prisoners who arrived had the benefit of stray sticks and branches left from the hasty clearing with which to make some form of shelter); it appears to be about six football fields square. One thing that immediately makes it look different from a “battlefield” park is that the cannon there are all pointed inward toward the center of the camp, to prevent prisoner escape. Sobering.

There was also only one source of water: a thin, shallow stream that meanders through the south end of the camp. Unfortunately, the water was used for everything: bathing, urinating, defecating, washing wounds (and the Confederate guards used it further upstream as a privy as well, so it was filthy when it got to the prisoners) ... one can only imagine the diseases borne by that water. As I walked the length of the stream, it seemed fresh enough at present (though the grass on either side looked a bit too healthy). Among the monuments on site that point to natural (or perhaps divine) intervention is a permanent, enclosed water fountain on a spot where a fresh little spring was discovered right in between the inner perimeter and the “kill zone,” just close enough that men could reach out with their hats (if they had hats) and collect a little fresh water. No doubt the spring helped some survive who otherwise wouldn’t have.

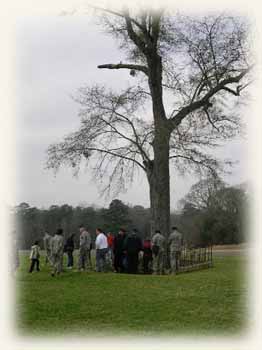

Another even more impressive and beautiful natural monument consists of giant oak trees that have new metal fences around them. Prisoners dug tunnels to try and get out and also to hoard acorns for food. In an otherwise empty field, two of these tunnel sites produced mighty oaks from the hoarded acorns.

Times of desperation often bring out both the best and the worst in men, and the latter was exemplified by a group of prisoners who called themselves the “Raiders.” They banded together, tricking newly arriving prisoners into letting their guard down and then overwhelming them, beating and often killing them in order to take their money, clothing and accoutrements. They would trade these items with the guards and thus have access to better food, whiskey, and shelter. Finally, the other soldiers rebelled, overwhelmed the Raiders and asked the camp commandant Colonel Henry Wirtz if they could hold their own trial in order for everything to be fair, with both sides having someone to speak for them and newly arrived soldiers who hadn’t witnessed any of the previous acts to be an impartial jury. Wirtz granted them permission, and a full trial was held that lasted for two days. In the end, the six Raider ringleaders were hanged, and the rest were made to “run the gauntlet.” It’s one of those events you wouldn’t believe if it were fiction, yet it wasn’t. (As a side note, Colonel Wirtz was the only soldier from the war tried, convicted and hanged for war crimes involving his intentional mistreatment of U.S. prisoners.)

As we moved to the cemetery, it was striking (as it always is in military cemeteries) how many graves there are. The differences between the graves of the prisoners and the graves of U.S. soldiers from other times (some very recent indeed; families of deceased veterans can petition to have their loved ones buried here just as they do at Arlington) are obvious. The prisoners’ headstones are much closer together, and there are large, beautiful, individual monuments throughout the prisoners’ section, donated by various Northern states starting in 1899. Also, the graves of the six “Raider” ringleaders were placed slightly to the side of the original graves, as if they were not deserving of the status of the rest.

One of the officers on our tour (and his accompanying children) placed weeds on those six graves. When I asked the purpose, he explained it was an old tradition practiced when you wanted to block the spirits of evil people from rising. One does not learn things only from the tour guides.

A national cemetery of any kind, but especially one with a history such as this, is an unparalleled place to wax introspective among the rows upon rows of neatly ordered graves, sparkling monuments, beautiful old trees (Andersonville has by far the largest magnolias I’ve ever laid eyes on) and other people doing much the same thing. Watching those people you’ve just toured with searching the graves for their own ancestors and placing flowers or small American flags at the sites is somehow both disturbing and comforting.

It was also satisfying to know I’d come a little closer to understanding what it was about the simple wooden spoon Private Baldwin felt was important enough to bring home as a treasure, a relic of a time and place where people from the same country (and often the same family) treated each other so horribly as to carve a niche in history as one of its bleakest events. He may have found the spoon, or he may have brought it with him. He may have bought it off a fellow inmate or a guard at the camp. He may have made it himself at the camp (though the quality and finish of all but the concave part at the end make this unlikely). He may have felt a little more human in being able to eat with a spoon as opposed to his hands; he may have shared it with his fellow prisoners or used it to help dig tunnels. While we will likely never know these details for certain, we do know that he felt strongly enough about the spoon to believe (as I do) that it and other relics of the past should be preserved if for no other reason to give clues and tangible evidence to those who yearn to know more about the past and the people who lived in it.

Copyright ©2007 Barbara Knott. All Rights Reserved.

Contact the Webmaster.