The Grapevine Art & Soul Salon

Tracking History: Jonathan Knott, Host

Atlanta History Center Visualizes the Civil War a Century and a Half Later

One hundred and fifty years have passed since the Civil War began in 1861. That seems like an awfully long time, doesn’t it? Here in the South we tend to feel closer to it than people do in other regions; it left a much bigger scar here, one that has never fully healed. It forced change on us as a people while simultaneously defining us as those who are often “stuck in the past.” As the vanquished, we have the reputation of being proud and bitter, and sometimes it is deserved. Why is this? What was so devastating that it tore our country in half and sometimes literally pitted brother against brother to the death?

Reading books on the subject is always helpful, of course, but museums bring the events closer and give important visual cues to stimulate the imagination. I’ve spent a fair amount of time wandering around the battlefields themselves, playing events over and over in my head as I gaze at the actual locations of historical events and attune myself to the nuances of living history. But if you haven’t read a lot on your own already, you might get only a cursory idea of what happened from the tours and videos typically shown at such places.

One of the most thorough and fascinating exhibitions of Civil War materials in the country is right here at the Atlanta History Center, and surprisingly few people even know of its existence. It’s called “Turning Point: The American Civil War” and is located indoors (which is a nice feature given the notoriously hot weather around here). One of the things you notice immediately is that there’s a structure to this exhibit; it’s not just a layout of random photographs and artifacts. There are facts and questions posted all along designed to try and really draw you into the event and make you feel closer to what happened.

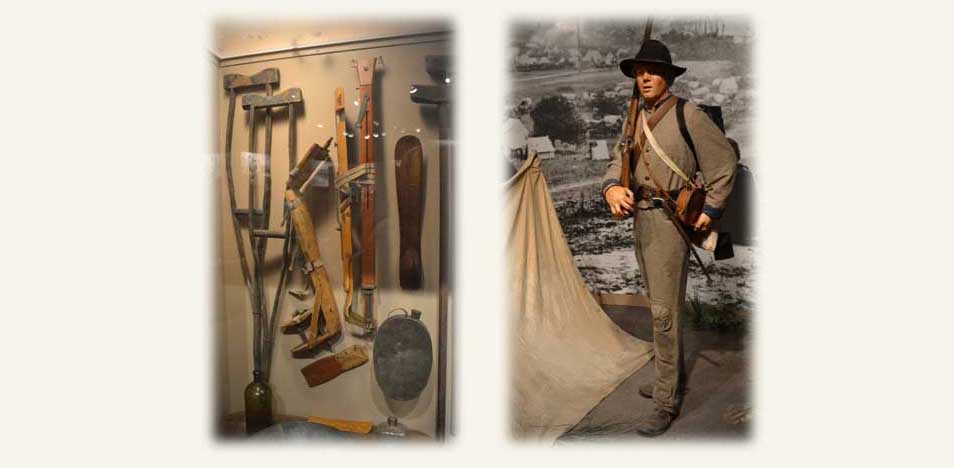

Some of the first displays show all sorts of strange and ultimately useless contraptions soldiers carried in the first few weeks of the war when everyone thought it would be over quickly and didn’t understand how hard it was to march with only what you were issued, much less a selection of additional comfort items. This becomes more apparent in a display where a Union and a Confederate soldier (one of several excellent uses of mannequins throughout the exhibit) stand fully accoutered side by side and you can see how small and skinny they were. Then, sitting next to the wall, there are a rifle, a cartridge box and a haversack that you can lift up and test the weight. When you try to imagine yourself weighing 130 pounds and living off parched corn, fatback and unsalted crackers and hauling that stuff (a good 60-70 pounds) miles at a time on bad or no shoes and then trying to summon the energy to fight when you got there, it makes you realize why cavalry was such a sought-after position. And as for the aforementioned shoes, there is a display comparing Union to Confederate styles (the Union shoes being much better than the cheap leather Confederate shoes) and then an example of blocky, wooden shoes you would wear around camp so as not to wear out your “good” ones before marching. If most of us now spent a day walking in the “good” ones, we’d have to spend a week at the chiropractor.

But while there are many, many displays of weapons and uniforms for the hardcore military enthusiasts (and many of the weapons have cutaway examples to show how they functioned), what really sets this aside from most comparable exhibits is the attention paid to detail showing as much of the human element as possible, both military and civilian. There are the grim displays of medical equipment, reminding us of how primitive medical technology and methods were and of the horrible numbers of dead due to such crude practices as doctors not washing their hands between operations because they were not aware of the presence of germs or not understanding how to combat dysentery, so that disease claimed more soldiers than combat did. There are displays of personal items soldiers carried: letters to and from home, bibles, hymnals, card decks and dice, tobacco pouches, whiskey and soda bottles, hand-carved pipes and talismans.

I have visited the exhibition several times, and what strikes me most every time I go is the depiction of civilian life that is so often ignored in other exhibits. They have a display showing how Confederate women offset the South’s lack of industry by making cartridges and other war materials themselves. There is a truly haunting display of a woman at home in her living room, wearing black and waiting indefinitely to hear what’s become of her husband or one (or more) of her sons. Women at the time had no pension from the government and little means to make money. They simply did the best they could and waited, hoping the men would come home eventually and not be too much shattered. This area of the exhibit does a fantastic job of bringing civilian suffering to life with powerful visual cues and information.

As you wind your way past displays of manufacturing techniques and naval weapons and equipment, you gradually make it to a great full-size display of the trench warfare that took place later in the war, and then to a very moving display about Atlanta. An enormous flag that flew over the city before it burned is there, along with a big chunk of debris full of burnt and twisted items from a city that was completely destroyed and vastly different from the one that sits in its place now. Behind the objects are huge, blown-up photos of the devastated buildings and railways, with the tracks twisted into the famous “Sherman Necktie.”

It’s important to reflect on such an event: imagine if an army marched into Atlanta today and completely laid waste to it, destroyed every single building and landmark, especially the highways and rail systems. Difficult to comprehend, no? Yet this unimaginable event happened here not so long ago. The final leg of the museum deals with the end of the war and what it meant to those involved. Six hundred seventy thousand Americans had died. A quarter of all white Southern males were gone. Three and a half million slaves were now free. The South was occupied by Northern troops for ten years during the Reconstruction period, which led to the formation of the Ku Klux Klan, among other things. How does a region or a nation that suffered so go about healing and rebuilding? The region didn’t really recover economically until after WWII eighty years later. As with all major historical events, things could have ended very differently from the way they did. This was indeed a major turning point; imagine if the South had won, or if the war hadn’t happened but we’d stayed pretty evenly divided as a nation between an industrial North and a slave-labor-supporting agricultural South? We might be still experiencing the tensions, like North and South Korea, of being yoked geographically and linguistically and culturally while living far apart in lifestyle and values.

This exhibition does a wonderful job of posting newspaper headlines, as well as quotations from powerful people involved, as it paints a detailed picture of both what happened and what might have happened. Here, for example, are two distinctly ununited views:

"This is an institution of chivalry ... to protect the weak, the innocent ... expecially the widows and orphans of Confederate Soldiers." Creed of Ku Klux Klan, 1868

"What does it all amount to, if the black man, after having been made free by the letter of your law, is to be subject to the slaveholder's shotgun?" Frederick Douglass, African-American activist, at the Republican National Convention, 1876.

And this, from an Illinois newspaper that same year: "The Negro is now a voter and a citizen. Let him hereafter take his chances in the battle of life."

A summary comment by the Exhibition writers: "By 1900 feelings on both sides had cooled. Many Northerners praised the good intentions of the 'Lost Cause'; many Southerners celebrated the preservation of the Union. Whites in both sections downplayed the role of slavery and emphasized the common experience of a good fight, justly waged. Following the example set by the veterans, whites created a new sense of national unity. It was a unity that took place at the expense of African Americans." One of the tragic failures of Reconstruction was that aspirations of the newly-freed slaves had to be put on hold until the Civil Rights movement a century later won for African-Americans the rights and practices of full citizenship.

Not everyone has the time and energy to visit a battlefield. But here the exhibits are indoors, air-conditioned and located within walking distance of Peachtree Street in Buckhead. During this 150-year anniversary, you owe it to yourself to spend an afternoon walking through “Turning Point” and reflecting on this great tragedy in the history of our country. In this case, dwelling on the past makes the present ever so much richer.

Copyright ©2011 Barbara Knott • All Rights Reserved