The Grapevine Art & Soul Salon

Presentations: Barbara Knott

WORLD, WOMAN, WONDER: Three Elements in the Art of Henry Moore, Sculptor

Scroll to the bottom of the page for images of all but four of the sculptures mentioned here.

Consider a man who, at age 87, was one of the most sought-after figures in the art world, not only in England where he lived but throughout Europe, in the Americas and the Far East. In his lifetime he suffered through two world wars, was sent home from the first to recuperate from having been gassed, and during the second war's bombing of London spent countless hours in the underground tunnels studying the people huddled and sleeping there so that, as a war artist, he could draw them. He enjoyed many public honors, including the International Sculpture Prize in 1948 at the Venice Biennale and a knighthood which he modestly refused on the grounds that to be called "Sir Henry" every day, even in his workshop, might somehow change his conception of himself and that his work might suffer from that. His marriage and the birth of a daughter nourished him and his art. He numbered among his friends some of the outstanding writers of his time, including poets T. S. Eliot and Donald Hall, art historian Kenneth Clark, and art critic Herbert Read. He had enough income from teaching and exhibiting his sculptures to travel to all the places he wanted to go, and he dwelt in environs that exactly suited him and his art. He lived a long life full of love and work. He is buried in a small cemetery in the churchyard of St. Thomas in Perry Green next to his wife. A thanksgiving service for his life and work was held in London at Westminster Abbey on November 18, 1986.

How might such a person define happiness? Here is what Henry Moore said the year before he died in 1986 at age 88: Happiness is to be fully engaged in the activity that you believe in and, if you are very good at it, well that's a bonus. An artist's raw material is what he has seen and done so I still have to refresh my eyes every day. It is not enough to sit in my comfortable chair surrounded by outstanding examples of fine art. Although it is difficult, I have to go out every day for a drive, to see nature, the countryside, the trees, the sky, to be renewed and refreshed. The drawings I make reflect my love of nature (Wilkinson 79).

Though his drawings are extensive, he is best known, of course, for his sculpture, of which 20 pieces have been on exhibit in Atlanta throughout the summer and fall of 2009. That exhibition, MOORE IN AMERICA, is the occasion for my musings here on the monumental, very contemporary work of this modest man.

Besides creating sculpture, Henry Moore wrote and spoke extensively about the art of sculpture. His comments have been collected and published in a book that I recommend, whether your interests are professional or personal, your experience in the arts lavish or little. At the bottom of the page you will find reference information for Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations (2002), ed. Alan Wilkinson.

Let me begin with more biography (Wilkinson 31-40):

We learn from Moore's writings that he was the seventh of eight children, that his father had little education himself but high ambitions for his offspring. The household had its Bible and its Shakespeare. The father insisted on his son learning to play the violin until Henry protested that he had failed exams to get into the local secondary school because he had to practice the instrument (he hated the noise it made). We learn that his father agreed to let him stop until he failed the exams a second time and, against the threat of having again to take up the violin, passed them on the third attempt.

He had known since he was ten or eleven that he wanted to be a sculptor. The moment of insight could be traced, he says, to a visit he made to a Congregational Chapel where the Sunday School superintendent told the group a story about Michelangelo on the streets of Florence carving the head of an old faun while a passer-by stood watching: And after watching two or three minutes he said to Michelangelo, "But an old faun wouldn't have all its teeth in." And then, according to the storyteller, Michelangelo immediately used his chisel to knock out two of the teeth. The moral followed, of a great man listening to the advice of other people even though he didn't know them. Moore declared that he was not so much interested in the moral as in hearing that there was someone, Michelangelo, a great sculptor, to pinpoint something in his mind, and that from then on, he knew what he wanted to do.

We learn that his mother had tremendous physical stamina and worked from morning till night until she was over seventy, that when he was seven or eight years old and his mother was suffering from rheumatism in the back, she would often say, on his arrival home from school, "Henry, boy, come and rub my back." He would massage her back with liniment: not just her shoulder but her whole back down from the shoulder blades with the skin close to the bone, to the fleshy lower parts. I had a strong sense of contrast between bone and flesh.

His female figures most often are matriarchal women. They've turned out that way, he says, not because he set out consciously to make them so, but because that's the basis of my own upbringing and relationship to my own mother. She was to me the absolute stability, the rock, the whole thing in life that one knew was there for one's protection.

We learn also in these biographical notes that he loved words, admired Shakespeare, felt that novelists had the most influence on him as an adolescent, read Dickens, Scott (whom he liked best), Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy, Thomas Hardy, and D. H. Lawrence, as well as French novelists. He was in the army from 1917-19, studied at Leeds School of Art from 1919-21 and at the Royal College of Art from 1921-24. He traveled to London where he fell in love with the British Museum, then to Stonehenge, Paris and Florence. He taught at the Royal College of Art from 1924-31 and had his first one-man exhibition in 1928. In 1929 he married Irina Radetsky who was "garden mad," he said, and who subsequently built up the landscape where he initially placed his monumental sculptures.

I discovered from reading the Wilkinson book that Moore himself is the best teacher of how to appreciate sculpture. See how he helps us disengage from habitual ways of seeing (194):

... the sensitive observer of sculpture must ... learn to feel shape simply as shape, not as description or reminiscence. He must, for example, perceive an egg as a simple single solid shape, quite apart from its significance as food, or from the literary idea that it will become a bird. And so with solids such as a shell, a nut, a plum, a pear, a tadpole, a mushroom, a mountain peak, a kidney, a carrot, a tree trunk, a bird, a bud, a lark, a lady bird, a bulrush, a bone. From these he can go on to appreciate more complex forms or combinations of several forms.

Moore refers in his writings to the "intense emotional significance of shapes" and to artistic principles that can be seen in nature's shapes, like "balance, rhythm, organic growth of life, attraction and repulsion, harmony and contrast" (187).

A friendly, accessible man, Moore was nevertheless impatient with certain questions about his work:

People say "Are you trying to be abstract?" thinking then that they know what you are doing though, of course, they don't understand what the devil it is all about. They think that abstraction means getting away from reality and it often means precisely the opposite--that you are getting closer to it, away from a visual interpretation but nearer to an emotional understanding. When I say that I am being abstract, I mean that I am trying to consider but not simply copy nature, and that I am taking account of both the properties of the material I am using and the idea that I wish to release from that material (114-5).

Although, like any sculptor, his intelligence is spatial, tactile, kinetic, Moore's main theme (like ours at The Grapevine) is being and becoming human. Two motifs that he rendered time and again into wood, stone, bronze and occasionally into fiberglass are the solitary reclining female and the mother with child. There is a rare representation of a solitary male, or of a king and queen together, or a family grouping that includes the father. And he worked with many organic forms. But Moore, by his own admission, tended to humanize everything, and he saw timeless, universal qualities of humanity mainly through forms of the human female.

I have seen an exhibition of his work once before. In the summer of 1972, a much larger selection of Henry Moore's sculptures was arranged spaciously on the grounds of the Forte di Belvedere that overlooks the city of Florence in Italy. I was there for a week's excursion from a seminar based in Lugano, Switzerland. With the exception of occasional civic statues seen here and there in the United States and others in Europe, including the replica of Michelangelo's David, which was originally conceived as a civic guardian figure, dominating the Piazzale Michelangelo in Florence (the original had been moved indoors during the l9th century to prevent further deterioration from weathering and now is displayed in its own rotunda), I had not seen much free-standing sculpture designed for the outdoors. Nor had I ever seen so many pieces by the same artist collected in one place.

With many views of Florence and vistas of mountains and sky around me, I walked from one piece to another, stopping often to explore the hills and valleys that made up the bodies of female figures: eccentric, exaggerated and simplified, far larger than lifesize. Masculine figures are rare in Moore's work. Once, I was attracted from a distance by the unusual presence of a high vertical piece, a thin male figure with piercing eyes. Another male figure, a warrior, was depicted horizontally, in the act of falling. And there was a lovely pairing, a king and queen seated side by side. But my walk was "grounded" by recumbent female figures, some solitary, others holding an infant or child.

At the time, Moore was living an hour away in Tuscany where he retreated for two months each summer to work on marble sculptures. In a letter (Wilkinson 75) to the mayor of Florence, thanking him for the opportunity to show his work in this setting, Moore declares that Florence is his artistic home and that no better site for showing sculpture in the open-air, in relationship to architecture, & to a town could be found anywhere in the world, than the Forte di Belvedere, with its impressive environs & its wonderful panoramic views of the city. His other home was back in England at Perry Green where his site for showing sculpture in the open air included rolling pastureland occupied mainly by sheep.

I wonder what Moore would think of the exhibition I am considering now, laid out more or less in the middle of Atlanta, Georgia, on 15 acres of midtown property cultivated by the Atlanta Botanical Garden. This is not the Garden's first large exhibition of art. They mounted a showing of Dale Chihuly's glass sculptures in 2004, but the Moore exhibition is something else, in that Moore's work is the metaphorical fountainhead of modern open-air sculpture, from which emanates such pieces as Chihuly's literal large glass fountain that remains in the botanical garden.

The Atlanta exhibition program tells us,

Moore is often considered the first sculptor to create fine art intended to be displayed outdoors that were not memorials, monuments, or garden ornaments. He enjoyed tremendous success, becoming an international celebrity courted by the rich and famous. Moore was already 50 years old after the second World War when the pieces in this exhibition were created, and they represent some of his finest work.

MOORE IN AMERICA is billed as "the largest special exhibition of Moore's monumental sculptures ever presented in the U. S." Shown in New York and Atlanta, it is comprised of twenty pieces, eighteen in bronze and two in fiberglass, on loan from the Henry Moore Foundation in the U.K. The exhibition program also lets us know, The selection of works explores all the sculptor's major themes: mother and child, reclining figures, organic forms, interlocking forms, and figures as landscape.

The Atlanta Botanical Garden staff has taken care to place the pieces against the cityscape and the architecture and the sky, following Moore's inclination (Wilkinson 245):

Sculpture is an art of the open air. Daylight, sunlight is necessary to it, and for me its best setting and complement is nature. I would rather have a piece of my sculpture put in a landscape, almost any landscape, than in, or on, the most beautiful building I know.

And he says this, of the importance of sky (248):

The sky is one of the things I like most about "sculpture with nature.... There is no background to sculpture better than the sky, because you are contrasting solid form with its opposite space. The sculpture then has no competition, no distraction from other solid objects. If I wanted the most fool-proof background for a sculpture, I would always choose the sky.

In November, on a day full of sunlight, with a blue sky and some cumulous clouds drifting over the city of Atlanta, I set out with my sister Nancy to explore MOORE IN AMERICA. We walked the grounds of the Botanical Garden, looking and touching (there is no prohibition against touching, though there are little cards all about requesting children not to climb on them).

Moore's interest in organic forms came with his fascination for materials--stone, wood, metal--and the natural shapes and textures they take, and he was fascinated, too, with how stone carves itself in upheaval, rolling in water, and in breaking; how wood grows its layers and rings of tissue; how metal transforms through heating and pouring and cooling. All the figures here except two done in fiberglass are bronzes. The bronze sculptures are large and hard and cold, textured with fine lines made by the molds that shaped them.

Moore was once asked by his niece why he gave the sculptures such simple titles, and he responded (Day, Elizabeth. "The Moore Legacy." The Observer, 27 July 2008):

All art should have a certain mystery and should make demands on the spectator. Giving a sculpture or a drawing too explicit a title takes away part of that mystery so that the spectator moves on to the next object, making no effort to ponder the meaning of what he has just seen. Everyone thinks that he or she looks but they don't really, you know.

The figure called Knife Edge Two Piece, positioned near the entrance, contained plenty of mystery. We were struggling to say what it resembled, and it resembled nothing we had seen before. That would probably please Moore who would want us, I think, to relax our need to know, or poet John Keats who might recite for us his definition of "negative capability," as "capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts without any irritable reaching after fact & reason." But neither of us had achieved that degree of detachment at the time, and we reached after something--anything--to say.

Then I remembered a workshop I went to once at the Schiele Museum in Gastonia, South Carolina, entitled "Abo skills," referring to skills of aboriginal people like the Native Americans who knew how to build fires without matches, how to make ropes out of plant fiber, and ... here is the connection ... how to make sharp edges by knocking a hard rock against a softer one, so that pieces fall away and can be used like a knife to slice and cut. That gave some context to start with, and soon we were running fingers along the thin bronze edges of two wedge-like pieces that, placed together side by side, were about twelve feet in length and over half that in height. We could see how they fit (loosely) with a crevice between them filled with light, as if the light had sliced through the metals. We noticed, too, that they were not symmetrical.

From Moore's writings collected in the Wilkinson book, we learn that the sculptor did not like symmetry--perfect symmetry is death, he says (Wilkinson 198)--or exclusively representational sculpture: To make stone look like flesh and blood, hair and dimples, is coming down to the level of the stage conjuror (187). Nature is not symmetrical, he points out, and it is nature that interests him, including especially the human body, which is also not fully symmetrical. If you take the two halves of the human face and reverse them, he says, you will have a different person. A straight line, a pure curve, solid geometrical forms, a perfect sphere, cone, cylinders, cubes, are thought to be beautiful (Plato) but they can best be made by machines, not artists. Art shows the fallible, human, variations from the perfect (114).

And to critics who complain about contemporary art's departure from realism and naturalism, he says (193):

I dislike the idea that contemporary art is an escape from life. Because a work does not aim at reproducing the natural appearance it is not therefore an escape from life--it may be a penetrating into reality; not a sedative or drug, not just the exercise of good taste, the provision of pleasant shapes and colours in a pleasing combination, not a decoration to life--but an expression of the significance of life, a stimulation to greater effort in living.

Moore was often described as working in abstract forms, but his forms are always to be found in nature, not abstracted from nature, and his forms are mostly figurative: I myself in my work tend to humanise everything, to relate mountains to people, tree trunks to the human body, pebbles to heads & figures, etc. (114).

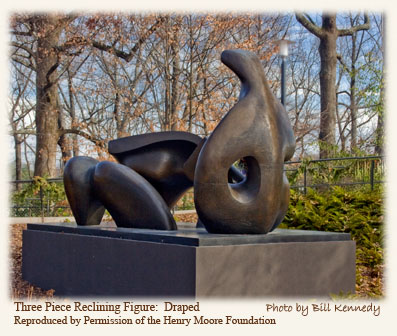

Inside the garden, near the Fern Dell Water Bowl, we looked at the sculpture called Three Piece Reclining Figure: Draped, wonderfully displayed with the woods behind it, and began to accustom ourselves to some of Moore's characteristic features: the female form, the reclining position (on the back rather than the side), the strangely small and minimally defined head, the rounded arms, open legs, the hard, glossy bronze, and the larger-than-life size, in this case a length of l5.5 feet. The three pieces are appropriately arranged to form a body with space between the parts, openings that invite one to imagine the joining and thus to participate in the forming of the sculpture. Counterpoised against the left knee is a configuration that might be called drapery, flaring and suggesting a shelter toward which the head is gently inclined. I discovered later that one casting of this piece, signed by Moore and numbered 4/7, was sold at Christie's Auction six years ago for $6,167,500, another indication of the largeness attached to Moore's work.

In the Wilkinson book, Moore discusses the human figure and its possibilities (218ff). He points out that for the human form there are only three poses: standing, sitting, and reclining. Of these, he says, the reclining figure offers the most freedom for a sculptor to work. In 1968 Moore says (212) that more than half of his sculptures, since his first reclining figure in 1924, have followed that pattern. He mentions, probably in response to questions, that he wants to be "quite free of having to find a 'reason' for doing the Reclining Figures, and freer still of having to find a 'meaning' for them." He insists that in working the same form again and again, "you are free to invent a completely new form-idea."

Unlike the Greek and Renaissance reclining figures, which are typically lying on their side, Moore's is most often on its back. The only other place I have seen that sculptural pose is in Mexico. On my first journey out of the United States, a driving trip south through Mexico City and west to the Yucatan peninsula and the Mayan ruins at Chichen-Itza, I saw a Chac Mool figure, atop a dizzyingly tall pyramid. The figure, from the period 900-1000 AD, is male and perhaps was intended to be an altar, for it contains a bowl on its belly. That Chac Mool, I learned, has since been moved to the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City and is likely the one that stimulated Henry Moore's interest.

It turns out that Moore came to prefer the unusual reclining-on-the-back pose when he discovered a Chac Mool figure (98). Moore says (70), Pre-Columbian Mexican sculpture has been the most important single influence in my own sculpture. For Moore, It was the pose that struck me--this idea of a figure being on its back and turned upwards to the sky instead of lying on its side. He describes the impact: Its stillness and alertness, a sense of readiness--and the whole presence of it, and the legs coming down like columns. Like the Chac Mool, the faces of Moore's figures are usually turned to the side.Unlike the Chac Mool, they are female.

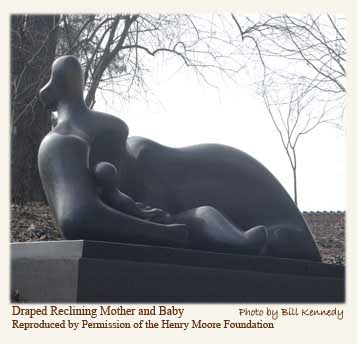

Moore's first subject is female, woman, the feminine, and his narrowing of that subject leads to woman-as-mother and to the mother-child motif. When his daughter Mary was born, he took up the theme of mother and child, repeating it many times. In the next figure that Nancy and I look at, Draped Reclining Mother and Baby, on a high bank with sky behind it, we see the maternal figure's right arm holding the baby while her whole body turns slightly, curving into a shelter for the tiny creature. She is rounded, encircling, containing, alert, alive. Moore's reclining female figure is not individualized, and he makes no attempt to render her realistic. Nor is she a modern Everywoman. He did not include in her presentation reminders of the many roles she might play but focused rather on her intimacy with nature, her fertility, her mothering qualities, and her creativity.

The Seated Woman that we come upon next has been placed in front of a curved brick wall below the garden cafe outside Day Hall. Over six feet tall, ironically, it reminds me in its rotundities of fertility figures like the Venus of Willendorf that were small enough to hold in your hand. The complex textural surface shows the effect of working in wet plaster with a trowel to make the cast for the bronze. I recall what Moore said about this one, that when he came to sculpt a figure representing a fully mature woman, he found that he was unconsciously giving to its back "the long-forgotten shape of the one that I had so often rubbed as a boy."

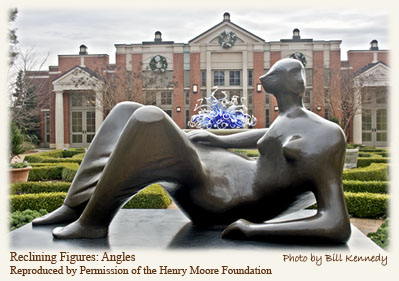

In front of Day Hall with its columns, near a parterre made of boxwoods and gravel paths and planting beds filled with rosemary, pansies, dusty miller, mustard, kale, and parsley, and backed by the large Chihuly colored glass fountain, is the Reclining Figure: Angles. The figure has massive knees with slopes evocative of mountains. Her face is turned so that she seems to be looking over her left shoulder with small pinpoint eyes, like pupils contracted against the light, but alert and still, without any identifiable emotion, as if listening for what might be coming in on the wind or light or scent in the air. There is an attitude of relaxed alertness in her massive presentation that reminds me, again ironically, of the elegance in a Japanese painting of a crane standing in the water's edge.

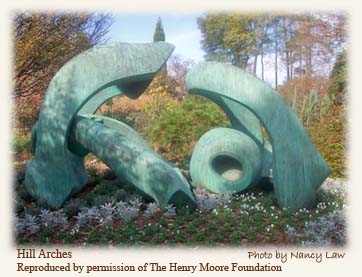

Moore's Large Totem Head, eight feet tall and 3,000 pounds, looks somewhat like a seed pod. The totem's eyes are like hollow places where the seeds used to be and its nose like the dividing membrane of a pod. The sculpture also resembles a uterus. From tribal cultures to complex civilizations, humans make art from comparisons, from likenesses among things in nature. Hill Arches, eighteen feet in length and nearly l0,000 pounds in weight, looks like a playful study of pelvic bones and genital parts. This piece, with its intense green sheen, has an appeal that causes me to return to it time and again to linger and look some more. I realize I am growing fond of organic forms and less concerned to say why.

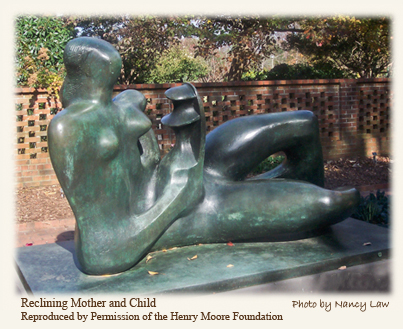

We enter a kind of bower near the Japanese Garden where we discover another Reclining Mother and Child. Nancy and I laugh at what must have been a mirthful idea on Moore's part. Here the mother, lying on her back with her upper torso raised, resting on one elbow, holds the child near her breast. The baby's mouth has the hard metallic quality of a trap about to snap shut on the mother's nipple. And since our imaginations are aroused, we are flinching at the same time we are laughing.

Back on the main path, we come to a resting place with long benches curved around huge magnolia trees. There is one of the frogs that can be found around and about the Botanical Garden, captivating large bronzegreen creatures that seem very much at home here and nearly human in size and demeanor.

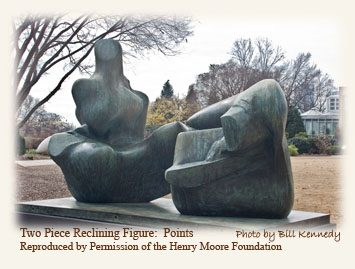

Now a great lawn opens up, and across it, on the other side, a pool and building come into view. There is a train for children, and a large sculpture, Two Piece Reclining Figure: Points. I recall Moore's comment that separating a figure into two pieces stops the viewer from expecting it to be naturalistic and encourages a stronger connection to its shape and volume.

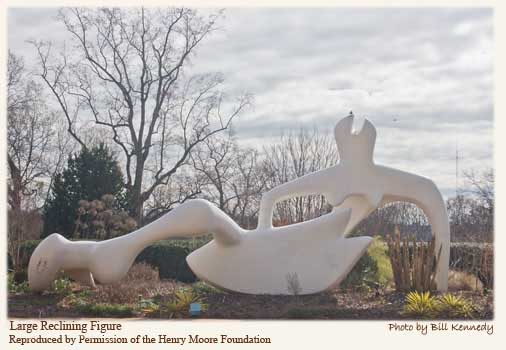

Alongside the curved walking path on the left is the Large Reclining Figure made of fiberglass. It is long (29.5 feet) and low and white. The abdominal area, under the carved breasts, is open and through it, we see the sky behind the figure. The head is turned straight up to the sky, and to my surprise, the mouth is rendered like the baby's mouth described above, as a simple curving line cut into the face. The figure's head is similar to female heads in Picasso's Guernica, whose faces are turned up just so, with mouths open, expressing horror. Here, there is no visible emotion. She would be at home, I think, anywhere there is sky. We see on the marker that Moore first cast this figure in lead in 1921, then collaborated with architect I. M. Pei to cast a bronze version for Singapore, and that another bronze "lies atop a hill overlooking fields surrounding Moore's home." This fiberglass version was made for ease in transportation.

On the path, young parents hurry past me with one daughter, perhaps five years old, while another daughter, ten or eleven, I guess, strolls slowly, eating chips from a plastic cup. She moves and eats with deliberate pacing, slow--too slow for the family who call back to her to come on. She does not change her pace as she stops at the Large Reclining Figure and says, simply, "I'm looking at the things." This lucky child has some of the patience, the relaxed alertness of the figures she is looking at.

The narrow, rectangular pool contains a fixed bronze figure, the Goslar Warrior, whose fallen body is thin and twisted and bereft of all but one limb. Still, his shield leans against him, a part of him, and his head is raised, eyes watching. His head looks somewhat like a helmet, though eyes and ears are clearly marked, calling attention to his humanity.

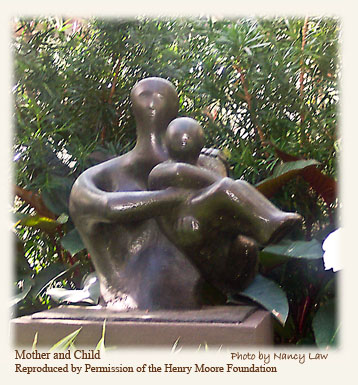

Taking a break from the outdoors, we enter the Conservatory and are struck with merging of animal and plant shapes in the staghorn fern. We discover bunches of tiny green vessels like Attic vases, called Nepenthaceae. We admire the phallic tropical flowers and imagine a whole world in a secluded mossy woods with a stream running through it. The environs here, where the imagination is so stimulated, is an appropriate setting for Working Model for Standing Figure: Knife Edge, the second fiberglass piece, also white, diminutive by comparison to the other figures at 5.3 feet, and lightweight. The piece looks like a long bone, knife thin in some places, to which a small head has been added to humanize the figure. Nearby is another figure called Mother and Child. In it, Moore depicts only the upper torso of the mother, whose able arms hold a swinging child.

Like the American painter Georgia O'Keeffe, Henry Moore collected and worked with found objects, including bones and stones. Here is how he describes his studio (Wilkinson 198):

... I collect odd bits of driftwood--anything I find that has a shape that interests me--and keep it around in that little studio so that if any day I go in there, or evening, within five or ten minutes of being in that little room there will be something that I can pick up or look at that would give me a start for a new idea. This is why I like leaving all these odds and ends around in a small studio--to start one off with an idea.

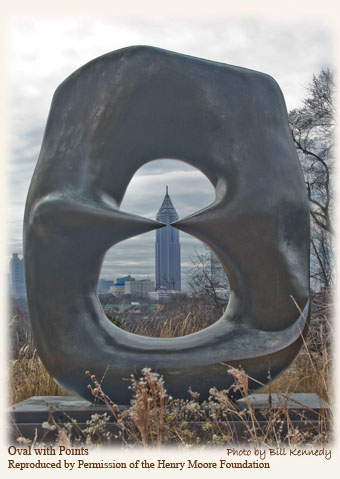

Also like O'Keeffe, who painted the sky as it looked framed by a large animal pelvic bone (an open round space, a hole), he was fascinated by the effect of holes in solid shapes. One of the mysteries of the hole is that it can have as much shape meaning as a solid mass, that it is space shape, the negative of the solid. To drill a hole in stone, he says, is to create a three-dimensional pull toward the other side. The Oval with Points, around ten feet high, placed in the Bog Garden among the pitcher plants, is an example of such an experiment. It was conceived from Moore's studies of an elephant skull.

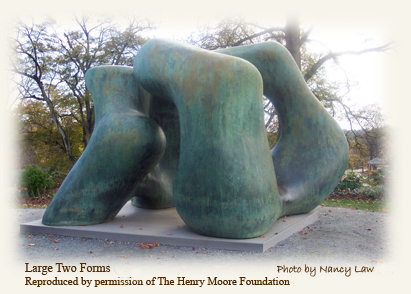

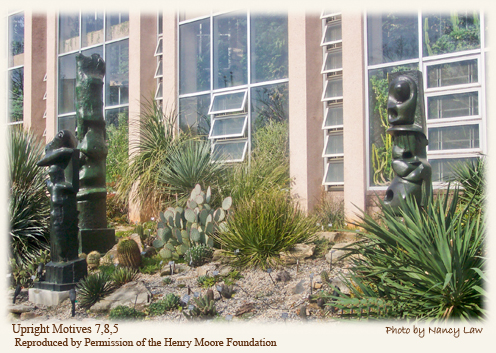

At the figure called Large Two Forms, near the Aquatic Plant Pond, a girl is photographing a boy through a large opening on one side while he stands framed by a smaller hole on the other. The Locking Piece nearby, backed by the conservatory and flanked by a small rotunda, is more square than oval, with rounded corners, sloping angles, and open spaces. The notion to make it came from Moore's interest in bones and then his finding two pebbles locked together that he played with until he developed a full-fledged idea for a large piece. Beautifully placed in the agave garden, which is sparely planted like a desert and full of white stones, are three columnar pieces called Upright Motives No. 7, 8, and 5, ranging from 6-10 feet in height, that resemble Native American totem poles (a connection acknowledged by Moore). The animal and mask features are suggested rather than detailed.

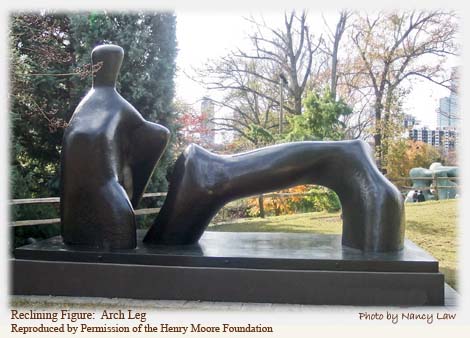

The final piece, Reclining Figure: Arch Leg, is the one in this exhibition most illustrative of the human body's resemblance to landscape. In it the legs are more recognizable as landscape than as human, but they flow beautifully from the reclining figure of a woman.

Moore worked large, and he understood the effect of scale. I have seen a picture (Wilkinson 207) of one of his sculptures, a reclining female figure only l3 inches long, photographed perhaps on a window ledge, against a vista of rolling land, and the small figure holds the landscape's vastness in balance--quite an achievement in manipulating scale. He says many interesting things about achieving the monumental look; for example (300): Sheep are just the right size for the kind of landscape setting that I like for my sculptures: a horse or a cow would reduce the sense of monumentality. So he kept sheep in his own pastures where he often placed his work.

Here is something else he says about size (Wilkinson 196):

Yet actual physical size has an emotional meaning. We relate everything to our own size, and our emotional response to size is controlled by the fact that men on the average are between five and six feet high. An exact model to l/10 scale of Stonehenge, where the stones would be less than us, would lose all its impressiveness. Because the stones are greater than us, we are impressed. But if you put the stones of Stonehenge into the Grand Canyon....

What the sculptor creates will depend to some degree on the potential in the material and to some degree on the sculptor's way of looking at things. Moore's way of looking and his way of shaping sculpture enabled him to create according to a principle mentioned by Michelangelo, that you could roll good sculpture down a hill without a piece being broken from it (Wilkinson 238).

It is refreshing to walk the grounds of a place--now in Atlanta as then in Florence--where one can see and reflect on one's immediate experience but also on this artist's achievements and, by extension, on Atlanta's increasingly sophisticated cultural identity, enhanced by the Botanical Garden's bringing Moore's work here, as it was enhanced when the Carlos Museum brought the King Tutankhamun exhibition to Atlanta earlier in the spring.

How different are the two exhibitions! The Egyptian display, indoors, was made up of items meant to be taken across the threshold of human life and carried by the ship of death to a realm that was mysterious and compelling but abstracted from this world. That arrangement was missing much of what is in the Moore exhibition, outdoors, of items showing a sacred devotion to woman and wonder at the life of the body in this world. The Moore display has the leisure expressed in a sign we saw in the Fern Dell at the beginning of our walk in the Garden: Gardening is the Slowest of the Performing Arts.

The display of Moore's sculptures in this spacious and lovely setting has given Nancy and me multiple pleasures, of looking and thinking, walking and conversation and laughter on this slow, beautiful morning. We are filled with new experience of the world as Moore saw it and with insights into new potentials in ourselves. When I saw that child on the garden path, willing her parents to wait while she took in what she was seeing, I realized anew how pacing affects our living (or failing to live). And I believe that Moore's reclining female figures embody the attitude that our culture has essentially lost in that these women know how simultaneously to lie down and wake up. That is the attitude of relaxed alertness that makes us aware, curious, and receptive. I am glad I took this walk with my sister, whose affection is dear to me. We have grown closer as each older relative and some younger ones from our family have died, leaving only us as near kin. My mentioning this fact is not merely a matter of nostalgia. Let me return to another of Henry Moore's thought-provoking observations (Wilkinson 200):

My belief is that no matter what advances we make in technology, and in the controlling of nature, and so on, the real basis of life is in human relationships. It's through them that we are happy or unhappy, and that we fulfill ourselves, or we don't. There is a great deal still to be done with three-dimensional form as a means of expressing what people feel about themselves, and nature, and the world around them. But I don't think that we shall or should, ever get far away from the thing that all sculpture is based on, in the end: the human body.

The human body has everything to do with what it means to be human. Our separate bodies are containers for our individuality and they are the means by which we embrace others. Through the bodies we express our emotional life, and with them, we make art. By establishing how closely the female body resembles and participates in the natural world and the world of imagination, Henry Moore vitalizes our view of humanity and, if we allow our minds to become receptive (to recline, like his figures), his work fills us with wonder.

One of Moore's friends, the poet Donald Hall, concludes an essay on poetry (Lammon 142-3) with the following remarks and anecdote:

"Finally, of course, I speak of nothing except the modest topic: How shall we lead our lives? I think of a man I admire as much as anyone, the English sculptor Henry Moore, eighty-four as I write these notes, eighty when I spoke to him last. 'Now that you are eighty,' I asked him, 'would you tell me the secret of life?' Being a confident and eloquent Yorkshireman, Moore would not deny my request. He told me:

The greatest good luck in life, for anybody, is to have something that means everything to you ... to do what you want to do, and to find that people will pay you for doing it ... if it's unattainable. It's no good having an objective that's attainable! That's the big thing: you have an ideal, an objective, and that objective is unreachable ...."

Consider the things Henry Moore made along the way to that unreachable objective.

Following its time in Atlanta, the MOORE IN AMERICA exhibition will be installed at Denver Botanic Gardens where it can be seen from March 1, 2010 - January 31, 2011.

WEBSITES AND WORKS CONSULTED

Atlanta Botanical Garden: www.atlantabotanicalgarden.org

Day, Elizabeth. "The Moore Legacy." The Observer, 27 July 2008.

Henry Moore Foundation in the UK: www.henry-moore-fdn.co.uk

Lammon, Martin, Ed. (1996). Written in Water Written in Stone: Twenty Years of Poets on Poetry. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

New York Botanical Garden: www.nybg.org

Wilkinson, Alan, Ed. (2002). Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations. Berkeley: University of California Press.