The Grapevine Art & Soul Salon

Views and Reviews: Barbara Knott

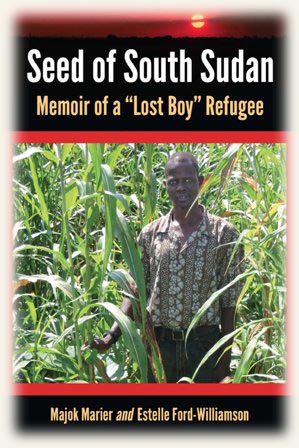

From Near to Far: Majok Marier and Estelle Ford-Williamson, Seed of South Sudan: Memoir of a “Lost Boy” Refugee, McFarland and Company, Inc., 2014

Into a season when we in the Western developed countries have been reminded of and forced to face the ravages of ebola in Guinea, Sierra Leona and Liberia where inadequate health structures and procedures and governmental support have not only threatened to wipe out whole populations but also to loose the deadly disease on the rest of the world while we can only look on in horror as our own governments try to help rally forces to contain and eradicate the outbreak—

into such a season when we cannot yet prevail over circumstances so far beyond our control in no-longer-so-distant lands (not to mention the tribulations that spend our energies and resources at home)—

into this season comes a story of another time only a couple of decades ago in which, on the same continent of Africa, a civil war in Sudan saw the loss of two million lives and the displacement of 80 per cent of the South Sudanese people, including thousands of boys who fled on foot nearly a thousand miles to take refuge in Ethiopia, from among whom, after moving several times, 3,800 of these boys, by then on the verge of manhood, eventually emigrated to the United States, one of them to tell, in this book, the story of his displacement at age seven, his sufferings, his redemption, and his ambition now, in his mid-thirties, to give back to his native land all that he can muster from his new life in a new place, including education, job training, and his connections to agencies and people full of interest and admiration for his courage, his endurance, and his undying hope.

That young man is Majok Marier, a member of the Agar Dinka tribe in South Sudan, presently living in the Metro Atlanta area, one of the places where South Sudan’s “lost boys” settled and where he works as a plumber’s apprentice to support his family in Africa. One of those people who took an interest in his story is Estelle Ford-Williamson, a former UPI reporter with three books to her credit, who writes and teaches in Atlanta. She worked with Majok Marier in making the book, which presents Marier’s story in the first person, set in Roman type. Here and there in the book, always discreetly, his collaborator provides information and commentary where needed to elaborate the complex politics of the region or to enhance some of the story’s details. Her commentary is set in italics, making it easy to distinguish who is speaking. He holds stage for most of the storytelling, which is as it should be. It is his story that we want most to hear, and in his own words.

The book is a masterpiece of collaboration, reflecting in its content, structure and tone many of the healing values so much needed by a world gone awry in so many places and ways as people everywhere undergo the stresses and find the strengths in globalization, a word that we hope will someday mean the coming together of creative community throughout the world.

Seed of South Sudan: Memoir of a “Lost Boy” Refugee is one considerable gesture toward such a synthetic movement. In it we hear first-hand accounts of what it was like to walk for months and months in the middle of the night over nearly a thousand miles, carrying, besides the risks of death by wild animals, enemy soldiers, thirst, starvation or disease—or, worse than anything, loss of hope—the seeds of a culture that Majok Marier’s grandmother believed might be replanted someday in a new nation.

Majok began his trek at the age of seven when he had already established his identity in a pastoral tribe of cattle-keepers whose lives were so fully enmeshed with their work that children were named after colors of the cattle. “My name, Majok, signifies a black and white pattern in Dinka.” A terrible and bloody war (that ultimately lasted 21 years) came down on his village when it was overrun by the Sudanese Army from North Sudan, an area controlled and populated by Arabic Islamic forces that had precipitated warring on the mainly Christian/animistic South by declaring sharia laws to be imposed throughout the nation. The Sudanese Peoples’ Liberation Army forged out of the rebellion came under the leadership of John Garang, a Dinka orphaned at age 10, whose unusual fortune had led him to become educated in the United States, eventually receiving a Ph.D. in economics at Iowa State University.

Garang was a colonel in the Sudanese Army who had also graduated from the U. S. Infantry Officer School at Ft. Benning, Georgia. He defected and later emerged as head of the SPLA. An effective leader in many directions, Garang found an ally in Ethiopia and established a significant military resistance while at the same time he articulated plans to build a new economy “based on the existing pastoralist culture.” His time in high office, after a cooperative peace agreement was leading toward independence for South Sudan, was cut short by his death in a helicopter crash in 2005, but his influence lives on in his emphasis on independence and education and in the memories of some of these lost boys who saw and heard the powerful Garang while they were being found. “You are the seed of South Sudan,” he’d said. “You are the engineers, the road builders, and more.” (161)

The book is valuable in its potential for educating the world about this nation and its striving to enter the modern world without losing the values of its tribal culture, but its greater contribution is in its giving voice to refugees, voices that might be heard by those suffering in such huge numbers in so many places—throughout the Middle East, the Americas, Europe, Asia, Africa—people we see daily on CNN, families with children fleeing from one place to another and, even now, sometimes children, alone. We watch numbly because we have no other ready responses as we look on one horror after another: faces of the frightened, the starving, the wounded, the dying, bodies of the dead. Through courageous reporting we are able to see in photographs and on film the haunting, heart-breaking faces of dark-eyed children who surely are wondering if this suffering is what is meant by “life.” Then along comes a book that slips past our defenses and tells a story so personal that heart and mind are moved, in hearing this voice from among the refugees of the world, to announce that no, maybe all these children are not “doomed, so there is nothing to be done.” The first thing to be done is to feel, to grasp the situations in Africa and elsewhere, and to think in the way of the Dinka, patiently.

This patience is required in reading and listening to their stories. The adventures in this one are many, of which I will mention one brief story of an incident that happened near Majok’s village before the war, when a man and his wife and new baby were walking in the wild and encountered an elephant that used its trunk to lift and fling the man down and then the woman, whose baby in a harness flew off and hung there on a tree limb while both parents died. The baby survived. Someone came and found it.

Where Was the World While We Walked? Is the title of Chapter 3. In it we hear from Majok Marier: “Many boys were dying because of the lack of food, cold weather, and disease. … We used to bury our friends, and this was unjust to have a child bury another child at our age.” He and others wonder whether the United Nations couldn’t have acted faster to bring food and shelter, to save the lives of children. We know that refugees are still asking those questions of the U.N. and of its individual members.

So how did these “lost boys” defend themselves against the overwhelming odds that they would not survive a thousand-mile journey through a wilderness infested with dangers? They went hungry and thirsty, were alternately too cold and too hot, swam rivers, crossed pockets of the great swamp where lived mosquitos that in their eyes seemed big enough to eat a man alive, evaded enemy soldiers, played guessing games, sang traditional songs and made up new songs about courtship and cattle, but they never sang about food. Instead, they took heed of something Majok’s grandmother had expressed in this way:

If something happens to us or to your parents you have to be patient, make yourself to be strong. God will help you, and you can be a better person in the future. … If you are having problems, don’t think about the food we give you here. If you think about it too much, you are going to die. (40)

While passing dead people lying here and there on the road, his uncle traveling with them said, “You must harden yourself against the sad feelings that come when you see someone like that .... “Never give in to bad thoughts, never give up hope. You will die.” (35)

This scene reminds me of the injunction to Dante who, when making his way into the Underworld of his Inferno, was told to harden himself against all that would pull him away from his journey, including the cries of those who were beyond help, lest his own salvation be sacrificed. This is surely one of the most difficult of life’s challenges, for it sounds like the opposite of compassion but has a deeper reference to the destructive forces in despair and inertia.

Even after l3 years in the U.S., Majok Marier says,

I feel I am still on a journey, with a goal of making others see the conditions of the country I came from and the section of Africa I left. I also want to open others’ eyes to the sometimes desperate situations once some help is found in refugee camps in an effort to improve the lot of those whose lives are deeply affected by these experiences. (8)

He details some of the ways that refugee camps offering interim help for people on the run nevertheless prolong suffering through inefficiency in delivering necessities like food. Still, they ate, eventually, and they went to school, eventually, where he learned to speak English and made himself ready for further, more extensive and productive help as it came to him. He says,

I believe our journey offers a lesson in how our problems in Sudan, in Africa, and other parts of the world will be solved in the long run. One village at a time, one settlement at a time, we will learn how to get along with each other. First, it will take approaching carefully, respectfully, and knowing what the other person’s needs are, and the boundaries we need to observe. (67)

He has two important points to make to African leaders of the present time: “Africa is a center of war and diseases that are not cured, and our leaders are not ashamed of the number of Africans dying because of these. … African leaders, you need to make some changes.” (175-6) Now, he says of writing this book, “I want refugee children around the world to know that Majok Marier from the Lost Boys of Sudan is standing up for you.” (174) He adds, “I am glad to have passed through this difficult situation of killing, starvation, thirst and going without parents. I want my book to make change for everyone who has some issue in his or her life.” (174)

Majok says of the early years of his life:

Since I was not in my home village, I did not undergo initiation. That is the painful traditional scarring of the forehead, six incisions made across the forehead, by which an Agar Dinka shows he is able to withstand pain without complaint and thus signals he is entering manhood. In the camp we did not do these rituals. Because we were not in our home villages, we did not extract the lower teeth in the mouth at this time. Instead, my entry into manhood was enduring all the hardships we encountered in our long search for our safe home. Because I was now of age, in our camp I could participate in the dances that symbolized entrance into manhood, including the dancing and jumping that are unique to our tribe. I became quite good at it, as I could jump really high. (71)

Estelle Ford-Williamson winds up her comments:

So South Sudan, the world’s newest country, carved out of the largest country in Africa, home of the White Nile River and the world’s largest swamp, and holder of oil and other unknown mineral resources as well as a climate ideal for many agricultural crops, has many challenges, and many opportunities ahead of it. (171)

Majok Marier concludes with these:

So the Dinka now embrace education and engagement, although our traditions are still intact otherwise. These values include: respect for other tribes, care for our cattle, care for our families, consulting with each other in times of difficulty to reach agreement, high regard for elders, and the value of celebration—carrying on the intricate rites of dance and song and body decoration. (174)

One cannot help comparing the Lost Boys’ situation to that of the thousands of disaffected young men roaming throughout the Middle East now, and the unfulfilled young men and women (increasingly younger) who are working their way from foreign countries including our own, into the armies of jihadists. Where are their initiation rites, their powerful cultural traditions that might make them feel as if they have truly come of age? Where are their challenges and trials? Is that what they are seeking in war?

Rumbeck Traditional Dancing and Jumping

How to Save Each Other: A review of "The Good Lie," a film about the Lost Boys

Copyright 2014, Barbara Knott. All Rights Reserved.