The Grapevine Art & Soul Salon

Entertaining Ideas: Barbara Knott

Metaphor Makes a World

Along with the invention of writing came the possibility of reading stories and poems from ancient times and other places. A story I like very much, about Lord Krishna and his mother, comes from long ago in India (cited in David L. Miller, p. 73).

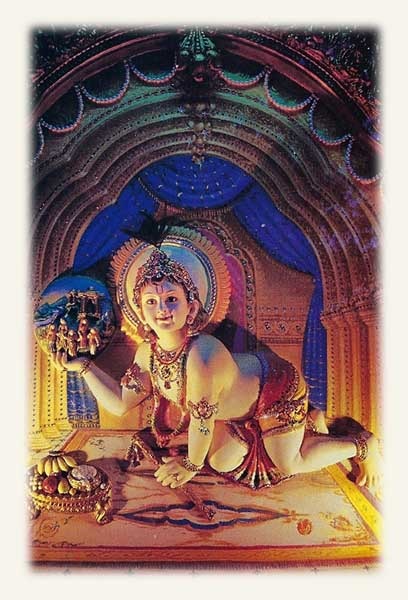

One day when the children were playing, they reported to Yashodha, the mother of Krishna (who was an incarnation of the god Vishnu), “Krishna has eaten dirt!” Yashodha took Krishna by the hand and scolded him and said, “You naughty boy, why have you eaten dirt?” “I haven’t,” said Krishna. “All the boys are lying. If you believe them instead of me, look at my mouth yourself.” “Then, open up,” she said to the god, who had in sport taken the form of a human child. And he opened his mouth.

Then she saw in his mouth the whole universe, with the far corners of the sky, and the wind, and lightning, and the orb of the earth with its mountains and oceans, and the moon and stars, and space itself; and she saw her own village and herself …. When she had come to understand true reality in this way, God spread his magic illusion in the form of maternal love. Instantly Yashodha lost her memory of what had occurred. She took her son on her lap and was as she had been before, but her heart was flooded with even greater love for God, whom she regarded as her son.

When I read that the first time, my mouth fell open in a shock of delight. Eventually, I realized that we all have a whole world inside us. And we can “mouth” what we are doing in conversation or shape it in writing to share with others at a distance or in the future. We have imagination to shape a world and play in it.

The most wonderful technique for worldmaking is metaphor, the result of a process in which we bring two apparently different things into an overlap so that each partakes of the other. Example: A human is a strong, proud oak tree with roots reaching deep into the ground of being while trunk and branches reach up and out to make contact through leaves with the living, breathing cosmos. If I’d said, “A human is like a strong, proud oak tree,” that would be what we call a simile and would contain its own truth but it would be more distant that my saying, “A human is a strong, proud oak tree,” using the metaphoric form to assert vigorously the kinship between humans and trees. It is, in practice, through metaphor that we experience our kinship with all life, our place in the world of creation.

Rilke says in his Duino Elegies (p. 85) that there is in poetic metaphor the waking of a likeness within us. He was working with this motif when he wrote … If we surrendered to earth’s intelligence, we could rise up rooted, like trees. And so is David Whyte when he asks, … What shape waits in the seed of you to grow and spread its branches against a future sky? (Both poets are cited in Miller, p. 73.)

Rilke, like D. H. Lawrence, was suffering from the sense of isolation and alienation from nature that came with an industrial revolution followed by a world war. Both worked through metaphors to reconnect with the natural roots of our being as humans. Lawrence speaks here on how love suffers when we are alienated from our world:

Oh, what a catastrophe, what a maiming of love when it was made a personal, merely personal feeling, taken away from the rising and the setting of the sun, and cut off from the magic connection of the solstice and equinox! This is what is the matter with us, we are bleeding at the roots, because we are cut off from the earth and sun and stars, and love is a grinning mockery, because, poor blossom, we plucked it from its stem on the Tree of Life, and expected it to keep on blooming in our civilized vase on the table. (“A Propos of Lady Chatterley’s Lover” in W. Roberts and H. Moore, eds. Phoenix II, 1968. Cited in Dolores LaChapelle, pp. 253-4.)

The metaphoric imagination, together with musical sensibility and the yearning to say something meaningful, creates poetry. Some who study the human psyche like David Miller in mythology and James Hillman in psychology, speak of a poetic basis of mind, referring to soulful imaginative possibilities and root metaphors rather than rationalistic apprehensions and interpretations.

I would like to illustrate with a single metaphor how much humans are akin, not only to trees, but to plants that blossom, to flowering. Flowering is one of the most powerful metaphors for life, with links to the female sex and to a woman’s most intimate body part. Rooting, stemming, budding, blossoming are staples in our metaphorical repertoires. Hence, the abundance of flowers associated with courting, decorating, scenting, and having sex.

For example, Eros, the Greek god of love who gave us the word erotic, is often found in a flowering field, suggesting the fertility of imagination. D. H. Lawrence declares that All living beings must move toward a blossoming (cited in LaChapelle, p. 254). And in the ecology movement, Arne Naess is an environmental activist who believes that Every form of life has the equal right to live and blossom. (cited in LaChapelle, p. 254). Bill Plotkin, in Soulcraft (p. 43) gives us this vision:

Even in our synthetic, egocentric society, the soul stirs in our subterranean depths, endlessly calling, pushing up like a flower through the cracks in the concrete pavement of our lives. We catch glimpses in our dreams and in fragments of poetry and song, in the distant howl of a coyote or in a bird’s sudden flight, in sunsets and the rapture of romance.

Metaphor functions to bring the reader into the poem and back into the land, the landscape, the world of nature. We have invented the word inscape to make the connection between the world out there that we experience through our senses and the world in here that we experience psychically, though imagination. Metaphor is fundamental to poetry and to being human.

With these thoughts in mind, consider some observations that have been made about the value of poetry and metaphor in all writing. Prose is certainly a more casual style, one that works well for conversation as well as academic treatises of any kind, especially philosophy, history, governmental documents, and law. Prose is also the language of storytelling. In storytelling, well-written prose often moves with muscularity into epic and narrative forms that retain a casual syntax but make use of the condensations and strengths of verse. Prose replete with images, metaphors and rhythms, has a more dynamic effect on readers. Here is Lawrence's view:

… It has always seemed to me that a real thought, a single thought, not an argument, can only exist easily in verse, or in some poetic form. There is a didactic element about prose thoughts which makes them repellent, slightly bullying. “He who hath wife and children hath given hostages to fortune.” There is a thought well put; but it immediately irritates by its assertiveness. It applies too direct to actual practical life. If it were put into poetry it wouldn’t nag at us so practically. We don’t want to be nagged at. (Complete Poems, p. 627.)

Words given poetically create images that carry sense awareness, sense knowledge, feeling awareness, instinct and intuition, to enrich thoughts and narratives. The poetic mode gives us a there, but no therefore to nag us. The philosopher, if he is to say anything, must be in some degree a poet, wrote Joseph Hone, in an essay on philosopher Benedetto Croce for the first issue of Envoy, a magazine for which James Hillman worked during his years in Dublin while at Trinity College. (The Life and Ideas of James Hillman, I, p. 233.) Similarly, we hear a study in deep ecology by Bill Devall and George Sessions producing this: Ecological consciousness seems most vibrant in the poetic mode. (Deep Ecology, p. 102.)

What happens when the two modes come together? Robert Haas, discussing the history of the “prose poem” in A Little Book on Form (p. 386), says this: In Baudelaire’s preface to Petits poems n prose 1869 he describes his ideal as “a poetic prose, musical, without rhythm and rhyme, supple enough and rugged enough to adapt itself to the lyrical impulses of the soul, the undulations of reverie, the gibes of conscience.”

David Abram gives this advice to writers (pp. 273-4):

Our craft is that of releasing the budded, earthly intelligence of our words, freeing them to respond to the speech of the things themselves—to the green uttering forth of leaves from the spring branches. It is the practice of spinning stories that have the rhythm and lilt of the local sound-scape, tales for the tongue, tales that want to be told, again and again, sliding off the digital screen and slipping off the lettered page to inhabit these coastal forests, those desert canyons, those whispering grasslands and valleys and swamps. Finding phrases that place us in contact with the trembling neck-muscles of a deer holding its antlers high as it swims toward the mainland, or with the ant dragging a scavenged rice-grain through the grasses. Planting words, like seeds, under rocks and fallen logs—letting language take root, once again, in the earthen silence of shadow and bone and leaf.

I have quoted Abram at length to give you a strong taste of his way with words in enacting what he is talking about, and of the delicious pleasure in reading this “writing language back into the land,” his way of finding himself and communicating to us what he has found: a treasure that far surpasses the abstraction of money and its purchase on our lives.

And now, the irony (and the subject for another idea to entertain on another day):

I took from my own master’s thesis on D. H. Lawrence’s concept of quickness this passage from The Trespasser. Lettie to George:

You are blind; you are only half-born; you are gross with good living and heavy sleeping …. Things don’t flower if they are overfed. You have to suffer before you blossom in this life.

These lines from David Whyte’s book of poems The House of Belonging bring an even more shocking thought:

at everything

growing so wild

and faithfully beneath

the sky

and wonder

why we are the one

terrible

part of creation

privileged

to refuse our flowering.

David L. Miller, Three Faces of God: Traces of the Trinity in Literature and Life (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1986, p. 73). He found the Hindu story cited in Wendy Doniger O’Flaherty’s “Inside and Outside the Mouth of God: The Boundary between Myth and Reality,” Daedalus (Spring 1980), 95.

Rainer Maria Rilke, Duino Elegies, trans. J. Leishman and S. Spender (New York: W.W. Norton, 1939), 85.

Dolores LaChapelle, Sacred Land, Sacred Sex, Rapture of the Deep: Concerning Deep Ecology—and Celebrating Life. Silverton, CO: Finn Hill Arts, 1988.

D. H. Lawrence, The Complete Poems of D. H. Lawrence, Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Poetry Library, 1994, p. 627.

Dick Russell, The Life and Ideas of James Hillman, Vol. 1: The Making of a Psychologist, New York: Helios Press, 2013, p. 233.

Bill Devall and George Sessions, Deep Ecology: Living as if Nature Mattered, Salt Lake City: Gibbs Smith, 2007, p. 102.

Robert Haas, A Little Book on Form: An Exploration into the Formal Imagination of Poetry, New York: Harper Collins, 2017, pp. 386 and 254.

Bill Plotkin, Soulcraft, Novato, California: New World Library, 2003. p. 43.

David Abram, The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World, New York: Random House, 1996, pp. 116-7 and 273-4.

D. H. Lawrence. The Trespasser, BiblioBazaar, 2006.

David Whyte, The House of Belonging, 1st ed. Many Rivers Press; December 1997.

The photo of Krishna above was on a picture postcard sent to me some years back from India by friends Bill and Pearla Kennedy. I keep it on my desk in a stand designed to hold a pen and pad, to remind me of what's what.

Photo of the rose by sandy mason

Copyright 2018, Barbara Knott. All Rights Reserved