The Grapevine Art & Soul Salon

Views and Reviews: Barbara Knott

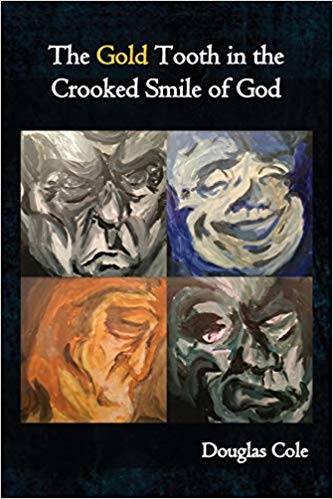

THE GOLD TOOTH IN THE CROOKED SMILE OF GOD

Review of DOUGLAS COLE’s new collection of poems

Douglas Cole’s latest collection of poems titled The Gold Tooth in the Crooked Smile of God is a challenge from beginning to end, where the outcome varies, as it does in all good poetry, according to what the reader brings to it or fashions from it while reading. Cole is unusually adept at leaving enough unsaid to require the reader to enter what Gaston Bachelard calls a reverie of will, in this case interpreted as “I will puzzle this out.”

Accustomed to exploring in my own poetry the body of God as it appears to us through incarnation in nature and in human creativity, I approached Cole’s work with great interest. His book is a rare opportunity to consider human life lived in cities, among “those sad, ugly, wretched, addicted/ poisonous and scabrous souls/ crawling through their days/ or sitting on a city bus beside that clean,/ grinning, happy-dull, complacent/ everything-goes-right for me/ citizen of the universe ….” The clearest “big picture” of what the book is about occurs in “Time of the Greats”:

Mohamed Ali Hemingway Miles Davis

Billie Holiday the great generals

great ambition great dreams and great vision

ability to say I am the greatest and believe it

and bickering people in constant irritation

standing in lines overcrowded oversaturated

watching the world die wishing it weren't

The poet asks, “What can I offer?” in the face of constant apocalypse? He answers with these poems, and I can add that what he offers is the gift of attention and densely framed detail, given without judgment, with empathy, and in beauty.

The poems provide interesting glimpses into the lives of ordinary people who commute on public transportation and pour out of buses into offices for their work week and gladly leave work for evenings and weekends to roam the streets for comfort zones where they dream of the bland better life of those with more money to spend. Here, “Bars exhale their patrons, the street/ trebles like a song, and inside every house/ when one light goes off, another comes on.”

But what does Douglas Cole mean by imaging God as a face, sometimes revealing in a crooked smile the hidden presence of a gold tooth with its associations of decay and repair? Is it there to warm your lonely heart? There to amuse? There to make you wish for gold? Literal gold as in gold toilets? No, that would be dreamed only by the “smug and rich and unconscious/ walking over your body to the club/ uninterested in your dreams or journeys.” How about metaphorical gold, as in meaning and purpose and beauty?

One clue to Cole's intention is in the epigraph, lines taken from singer Jim White's Searching for the Wrong-Eyed Jesus, a film starring, among others, novelist Harry Crews, where the search for God is a road trip in a classic car through the rural South, in search of beauty and meaning imaged as “the gold tooth in God's crooked smile.” Cole adapts this fascinating image to hover over the present condition in largely secular urban areas in the West: bland Sundays full of loneliness, drifting, or driving to a library full of “old books that whisper/ stories of another age and near/ death experiences no one will ever read/ yet remain the way all things remain/ in the vast vault memory of God ….”

He describes this world as “Pragmatic. American stoicism,/ a grim fortitude of disappointment/ and distrust …,” a place where religion, for many people, has no longer a vital sense of immediate reality but rather is a vague or distorted expression of what was once Almighty God, looming up there like a cloudy face, possibly grinning at the goings-on among his earthly creatures and perhaps, just perhaps, although out of sight but not completely out of mind, there may be a glint of gold lurking inside that grin … a tooth of hope … for beauty, for value and meaning that used to lure people to church, to make life feel worthwhile.

Cole focuses on the harshness that dwells among people who have been “gut-punched” by life, harshness expressed in “Thoughts of a Hanged Man” as cold, hate, hunger, fear, pain, nightmares, shame, regrets, bad choices, and waiting in line. “In Those Days” speaks of “people coupling and fragmenting/ in a particle accelerator of lives—/ and when the fires came, we scattered like cockroaches,/ found other rooms in which to sleep,/ to play and drink and seek oblivion.”

Here, there is little opportunity to enter Bachelard’s balancing reverie of repose, except in occasional significant lonely moments created by smoke, drink, drifting, where fantasy life takes over in daydreams of, for instance, “a Mai Tai under a palm tree.” Such dreams sometimes get translated into a cruder form. In “My Friend's Garage,” the speaker's friend, to create space away from his wife who is having sex regularly with another man (as he is having sex with another woman), fixed up his garage “like a tiki bar,/ with palm tree posters and coconut ashtrays/ and bamboo grass along the workbench,” declaring, “A man's got to have a place he can fart.”

What is beauty, you may ask, in such a world? The word is mentioned mysteriously in “Black Fish” where, after describing the hill people who come to town “in their finery/ and smoke-soaked coats/ drinking, laughing ...” he quietly transitions to “while beauty appears/ and crosses the street/ to the Salvation Army/ in Morton on Saturday night.” More explicit answers can be found in a poem called “Beauty,” arranged in a gripping sequence of images that begin with “Beauty is the burned husk of an old house/ with a crime scene strip around it/ I pass each night on my way to you.” My favorite appearance of the word occurs in “The Voyagers” where, in the face of rampant dereliction, the poet looks on as “beauty pulls a curtain back/ or shows up in worn shoes next to the bed” (an image I associate with Van Gogh’s art).

In Cole's “Invisible Land” the speaker sits in a bar waiting and thinking, with a “need fire going in the heart/ while we ride the big winds/ through the deep black sea/ because I’m waiting for beauty/ to come through the door/ with that inextinguishable spark.”

This book bears reading again and again to discover as I did that Douglas Cole is not writing merely about losers and winners out there where real life is envisioned as garbage, where fantasy life is bland and bereft of meaning—he is writing about us in our own bleakness, reading and wondering, “what's next?”

Near the center of the book is a long poem “LA Days,” chock full of images from a man's late life reminiscing that ends with “and so I've come back to tell you/ about this dream I had/ about a man who goes into a theater/ to watch the movie of his life/ and all the way through he keeps saying,/ I remember that,/ or, that never happened,/ or…oh, man, I wish I could do that again.”

As I read, I began to hear in my own mind the echo of Willy Loman's wife Linda in Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman, crying out against her husband's apparent worthlessness: “I don't say he's a great man. Willie Loman never made a lot of money. His name was never in the paper. He's not the finest character that ever lived. But he's a human being, and a terrible thing is happening to him. So attention must be paid. He's not to be allowed to fall in his grave like an old dog. Attention, attention must finally be paid to such a person.” This collection of poems is Cole's way of paying attention, more like Harry Crews than Arthur Miller, but with quiet empathy and the added intensity of poetry.

At the end of this journey through the poems, I sit with the speaker in “The Consolation of Philosophy” and listen to his magnificent speech and say, “I got it!” (meaning my own variations of “it”) and understand and feel the blessing he leaves, there on the page, for me.

We recommend reading this book in its entirety before, during, and/or after exploring The Grapevine’s Issue 21: Douglas Cole, The Gold Tooth in the Crooked Smile of God. Portland, Oregon: Unsolicited Press, 2018.

Website: www.douglascole.com

Copyright 2018, Barbara Knott. All Rights Reserved.