The Grapevine Art & Soul Salon

Reflections

Charles Knott: Theatrical Adventures

When Barbara and I went to a conference on C. G. Jung, Hermann Hesse, and R. D. Laing in Switzerland during the summer of 1972, we met Michael Volin, who, to this day, is the most interesting man I've ever known. Michael had been engaged as the resident yoga instructor for the conference attendees. He and his wife Daphne became our good friends. Four years later, when Jonathan was three years old, we expressed to them our desire to pursue various studies that were available only in New York City. They persuaded us to move to where they lived in Nyack, New York, conveniently located twenty miles up the Hudson River north of Manhattan.

Nyack is a theater town. Its main thoroughfare is even named "Broadway." Located there is the famous Tappan Zee Theater where Liza Minelli and others got their start in show business. It was shuttered when we moved there but still full of theatrical history, and restoration was rumored to be imminent. Nyack had also a vigorous, sophisticated community theater named Elmwood Playhouse, supported by a seemingly endless number of talented actors and directors who had day jobs, but many also had impressive amateur and performance resumes. They were capable and inspired, and occasionally their productions were truly superb.

I had long been interested in vocal performance, specifically dramatic readings of poetry, but I did not make the transition to stage performance until the age of 36 when I took my first acting role as W.O. Gant, the father in the play made from Thomas Wolfe's Look Homeward Angel. This important life event had occurred while I was still on the faculty at Truett McConnell College in Cleveland, Georgia.

Gant is a blustering comic figure with a huge voice and a notably belligerent attitude. The cast for the production was made up of both faculty and students, and I got the part easily, no doubt because I can be loud and because I had a good deal of belligerence to channel into the performance. The play has its tender moments, but the dominant force is Gant, a soulful man, but also a loud, boisterous, comic drunk. Even though I was a first- time actor, the role came naturally to me, and the experience was delightful.

A couple of years went by, and the day came when I found myself very far away from the North Georgia mountains walking into an audition at a highly sophisticated community theater in the small village 20 miles above New York City.

True, life had to some extent warmed me up for this experience. To give some context, Barbara had started a Montessori school soon after we arrived in Nyack, and I selected from my embarrassment of credentials (Master's degrees in English, Psychology, and Social Work) to take a job as a social worker. After two years I left that work and joined her as a Montessori teacher. We called on our love of theater to entertain the children.

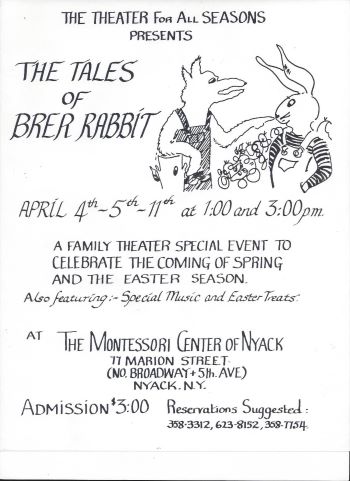

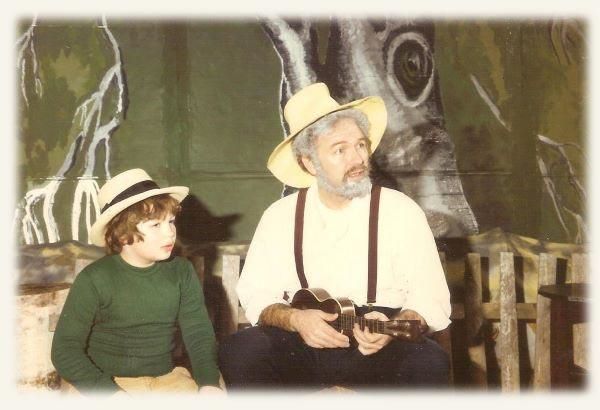

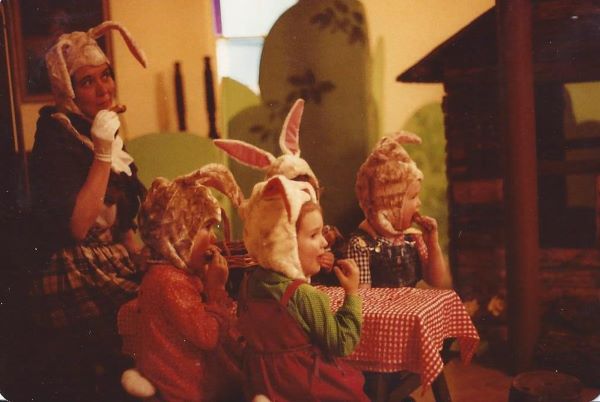

We did theater for children (The Emperor's New Clothes, to name but one of many, in which I played the naive emperor) and we also often did theater with children (Tales of Brer Rabbit, with me as Uncle Remus and Jonathan as the enchanted boy who listens as the story is narrated and acted out).

In my experience, all children are natural actors. My only problem was that they brought out the clown in me and were too easily pleased. I got tired of playing the clown and wanted a more critical audience that could help me develop as an actor. Doubts nagged me: I wondered if I could ever be a serious actor. I was tired of being a comic and of working child and adult audiences for laughs. When I heard auditions were being taken for roles in a musical version of Shakespeare's Two Gentlemen of Verona at Elmwood Playhouse, I decided to give it a try. I was intimidated by the reputation of the theater, but not for long.

The audition began by my walking through the door! I walked up to a man named Murray who was sitting at a piano and told him I wanted to audition for a part in the play. He started playing a rapid piece on the piano and asked me to dance. I said, "I don't dance." So then he started playing a few chords on the piano and said he would like to hear me sing. I said, "I don't sing." He said, "Well, let me hear you sing anyway!" I told him I didn't know a song. He said, "You've got to know a song! Everybody knows a song." I said, "Well, I don't." Then he said, "How about singing Happy Birthday? Do you know that?" I said "Yes."

Then he began playing Happy Birthday. I sang it at the very top of my lungs and the sound came out, not beautifully but extremely loud and on key. Murray looked at me in amazement, sizing up my long, full, salt-and-pepper beard and my extremely aggressive voice. He saw a comic villain at once. He said, "I want you to play the Duke of Milan." Hopefully, I said, "Is that the lover?" He said, "No. That's the father."

My heart sank. My original role of W. O. Gant, also a middle-aged father, had come all too easily, and now, 1000 miles away in a new, unfamiliar environment, life definitely was funneling me into stage acting, but I was stuck again with what sounded like it was going to be a replay of W. O. Gant, a middle-aged comic villain. I loved being so easily cast in a sophisticated theater, but there was definitely the lingering, hopeful wish to be a leading man, even at the advanced age of 41. I wondered if it would ever happen. I thought to myself, I'll play the comic villain one more time, and maybe it will furnish a pathway to what I really want.

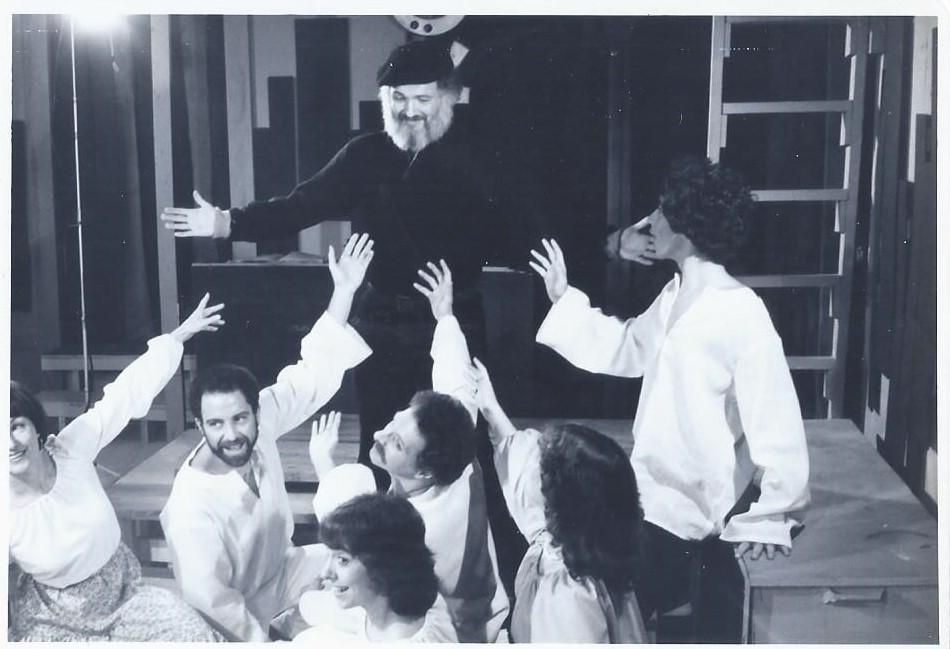

I remember one interesting moment soon after the cast had been assembled and we had become familiar with our parts and were working out the blocking. I had a comic song, half sung/half spoken, that was central to the play. It turned out I did have one of the lead roles!

The time came for me to give the first rehearsal run-through of my song, a satiric number about causing a war and then running for office on a "bring the boys home" platform. A live microphone was lying on the floor of a scaffolding that had been built just for me to do this song. Murray said, "Okay Duke, do your number!" I was somewhat astounded. I said, "You mean, just get up there and take center stage?" Murray was sitting at the piano looking straight ahead. He got very quiet, did a slow burn and then turned and looked directly at me. He said, "You goddamn better get up there and take center stage!"

This was a new attitude toward life for me. I had always been told to "tone it down," "leave some for others," "control yourself." True, I had done the boisterous, loud, comic role of W.O. Gant, but that was not enough to accustom me to the idea of dominating much of an entire theater production. I was being not simply challenged, but actually commanded to do that very thing. In the role of the Duke, the comedy of the entire production depended on my extremely aggressive domination of every scene I was in. Fortunately, it was exactly what I wanted to do. I at least derived confidence by being in the realm of my unwanted specialty, the loud, aggressive, sometimes sinister, sometimes comic buffoon. The players, in role, were terrified of my glance, and my lines were funny.

In keeping with the well-known erotic tendency generated by the close proximity of players, putting on makeup and changing costumes in intimate spaces, all while releasing repressed emotions, I could not help noticing that my stage daughter was a particularly voluptuous young woman. In accord with the script, I had the pleasure of a number of comic confrontations with her, and as her stage father, I settled one argument with her by hoisting her over my shoulder and marching off the stage with her as she impotently pounded on my back with her little fists. Only in theater can such things happen!

The most fun performance occurred one night when the auditorium filled with a high school group who had just given a performance of the play themselves. They sang the songs with us, and I felt like a rock and roll star controlling an audience that was both rowdy and worshipfully appreciative. We had a ball! When the play was over, the cast mixed with the audience, and we danced to a recap of the music played over the PA. I was dressed all in black, including dark glasses and a black turtleneck sweater augmented by the costumer with leather trim and exaggerated shoulder pads. I walked to the bleachers and chose a slender, elegant high school girl to dance with me. She squealed with excitement and then danced me into the floor. We did eight performances of the play, and each night brought a euphoria in its wake. I was truly sad when the last curtain fell. I still wanted to do a dramatic role. I wanted to be a leading man.

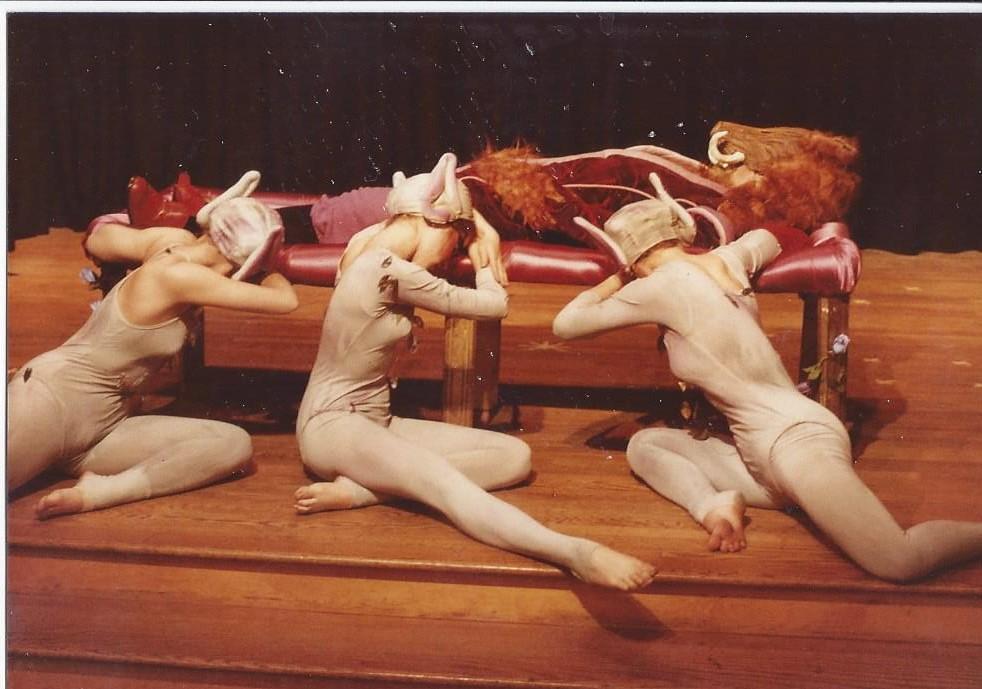

A moment of transition came when we decided to do a performance of Beauty and the Beast: A Masque. A Masque is a peculiar dramatic form used by the royal European courts of previous centuries. It is dark and mysterious, flashes elaborate, bizarre and colorful costumes, includes music and dance, in our case a rhymed script and a fairy tale level of magical happenings. History tells us that royalty loved it and would often take parts themselves and mingle dramatically on stage with professional actors hired for the performance. In our show, I would play Beast, and our talented stage designer would make an animalistic and frightening mask for me. In general, our imaginative costumers would be unrestrained.

This all sounded very good, but the first thought that ran through my head was, actors and dancers? Where will they come from? Music? Where will we get music? And who will play Beauty?

While these questions were flashing around in my head, I was invited to a dinner party and seated beside an unconscionably beautiful woman in her late 20s. Oh, my God, I thought. Might this be Beauty? Let me get her story. It turns out she was a former ballerina with the New York Ballet. Be still, my throbbing heart! Why did she resign her position? Because, she said, 18-year-old girls were arriving in droves every few weeks to audition for her job, girls who would do literally anything to take her place. She coped with this year after year and then, she said, the day came when her body told her NO. "My body wouldn't do those things I commanded it to do. The 18-year-olds trying out for my job didn't have that problem." What a pity, I thought to myself, to age out of your profession before 30.

But thinking about my own ambitions, my pulse raced at fever pitch. She might not want to dance for the New York Ballet anymore, but I bet by God she wouldn't find it too stressful to dance Beauty in our production of Beauty and the Beast! I described the production and asked her if she would play Beauty for us. She very graciously told me she would be happy to but, unfortunately, she and her husband (sitting across the table from us) were only going to be in town for a couple of days on a fundraising mission. She would be leaving, so she had no choice but to say no. I was crushed.

Then the well-known phenomenon of theater magic started happening. First, the daughter of one of our costumers, home from her university in New England, showed up with a reel-to-reel tape that had been elegantly, exquisitely edited for this very play. Wonderfully appropriate phrases from classical music had been edited so that a sound tech could move us beautifully from scene to scene. This was really too much of a coincidence to believe, yet there it was, miraculously, exactly what was needed. It really was a moment of magic.

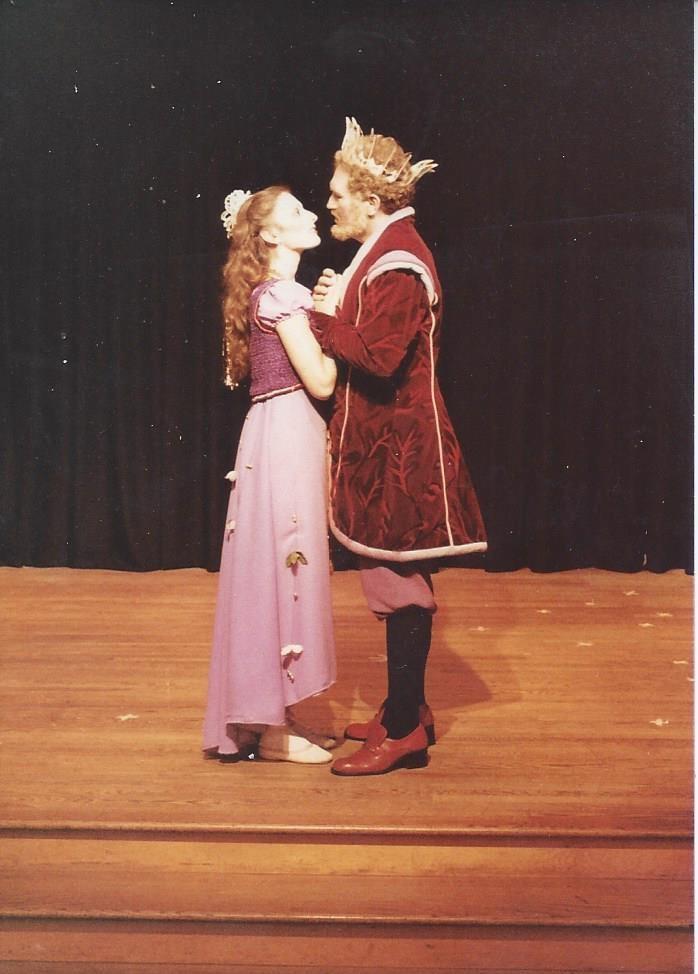

We also needed Beauty and a half dozen dancers to dance the fairy roles needed to make the Beast's kingdom function properly and to advance the action of the play. How about Cheryl, the Nyack dance school owner and instructor? She was tall, gorgeous, and had waist-length auburn hair. We asked her. At first mention of the project she accepted, and as soon as word got around, we were rushed by a large number of her students, young ladies aged 15 to 18 who were only too ready for performance. We went into rehearsal immediately.

As the masked Beast, I was frightening indeed. But then I had to undergo a metamorphosis into a "handsome Prince." I wasn't sure I could do this, wasn't sure I would be taken seriously as a lover. This was the first step toward what I had wanted for so long. I would be the lover, but only for one brief moment at the end of the play. I would be lying on a cot, the fairies would dance around me and take my mask off, and I would transform and rush to center stage to embrace Beauty. When the moment came, I rushed all right! I got a pulse of endorphin from the magnificent symphonic phrase that announced my transformation, and I transformed!

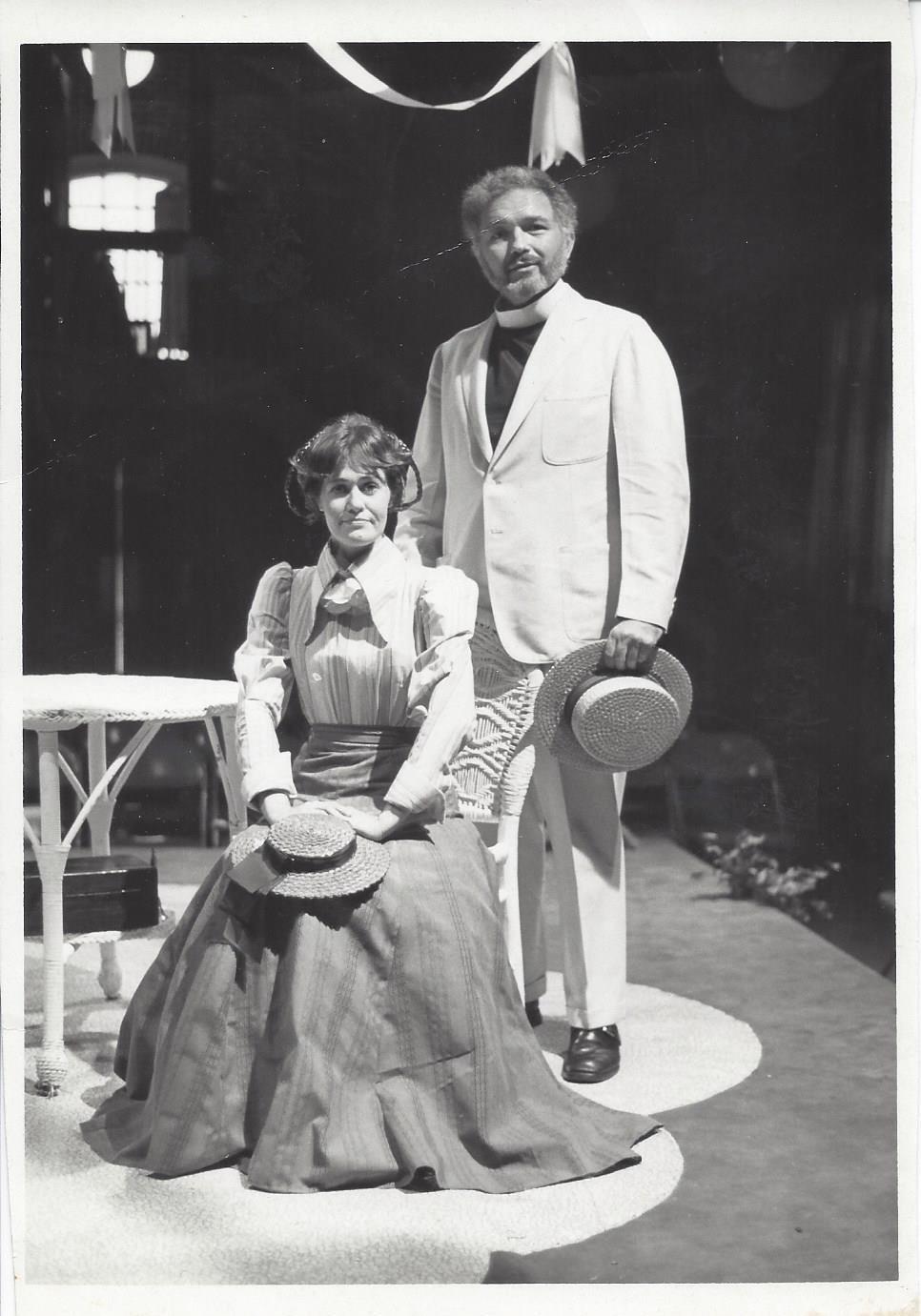

From this role, I drew new confidence and was emboldened to audition for a strictly dramatic role in The Runner Stumbles, a play with, thankfully, no humor.

No clowning allowed, just unrequited sexual desire, thick and heavy. I proved I could be an effective leading man.

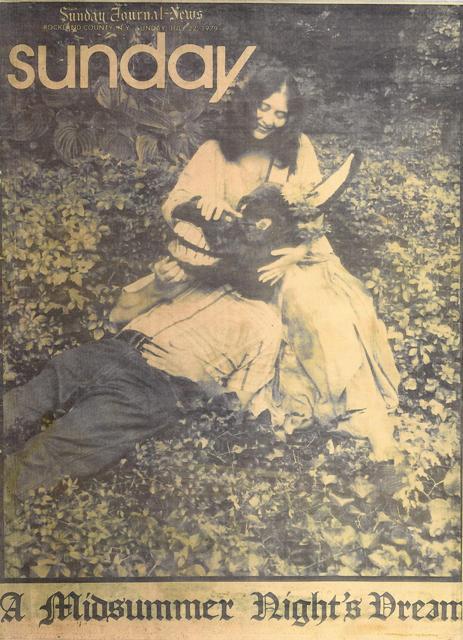

A highlight of our time in Nyack was a production of Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, performed on the side of a mountain to a large audience that included no less than the First Lady of the American Theater, Helen Hayes, a resident of Nyack. She attended our outdoor production and sent her compliments afterwards. She revealed that her first role as a child actor had been the fairy Mustardseed, played in this production by our son Jonathan.

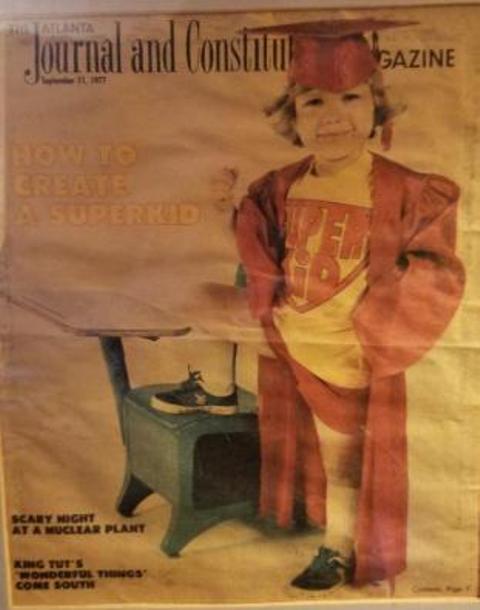

The Rockland County News covered the event and arranged to photograph Barbara as Titania, Queen of the Fairies (I played Oberon, King of the Fairies), sitting outdoors with Bottom the Weaver's donkey head resting in her lap. They featured the photo on the front page of the weekend journal. Jonathan, now five, performed as one of our fairy children, Mustardseed. Earlier, in Atlanta, while in Montessori preschool, three-year-old Jonathan had been photographed in a Superman outfit to represent a Super Kid and was similarly placed on the front page of The Atlanta Constitution's weekender, thereby preceding his mother by two years.

And so my career as an actor continued over the ten years we spent in Nyack working with other theater groups like Elmwood and producing many plays with our own director and theater group called the Theater for All Seasons. My work was recognized in good reviews and, a couple of times, in requests to play in professional productions. One was the role of Eadweard Muybridge in a New York produced short film called A Gentleman's Honor, in which the famed photographer and forerunner of film makers murdered his wife's lover. Accompanied by a Philip Glass soundtrack, it has been referred to as "the first music video." It was part of a new genre of video art, and it won a prize and was shown for six weeks at the New York Museum of Modern Art.

I have found it on YouTube at this link, though the quality has suffered from being compressed onto YouTube:

Charles Knott, A Gentleman's Honor (film)

Other performances included scenes from Shakespeare played in an enormous back yard beside the Hudson River with an invited audience. Here is a moment with Petruchio and Kate from The Taming of the Shrew.

These adventures have continued throughout much of our lives, including the five years spent in our suburban castle when we returned to Atlanta and created a mummer's play tradition, along with other theatrical pieces.

It's been quite a while since I participated in a full performance, and I miss it. In fact, I'd like to act for the camera again. I'm thinking of warming myself up by giving dramatic readings of poetry on video. I'll put them on YouTube with links to them on The Grapevine. That's what I'll do!

Stay tuned.

Copyright 2021, Barbara Knott. All Rights Reserved.