The Grapevine Art & Soul Salon

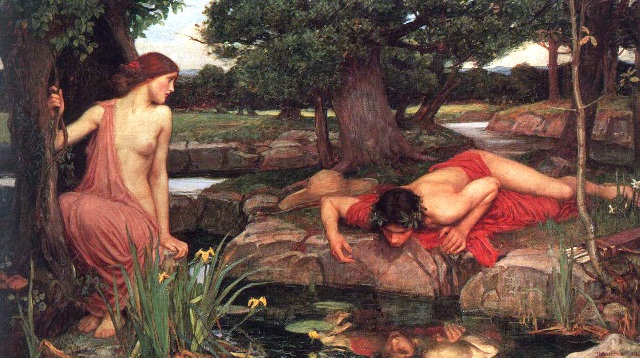

Is Narcissus the patron saint of imagination? His love was wholly given to and fulfilled by the reflected image that took him to the underworld.

James Hillman, The Dream and the Underworld (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 1979, p. 119)

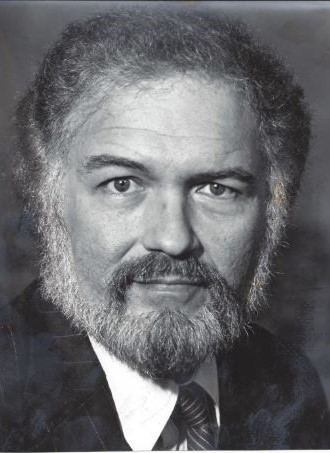

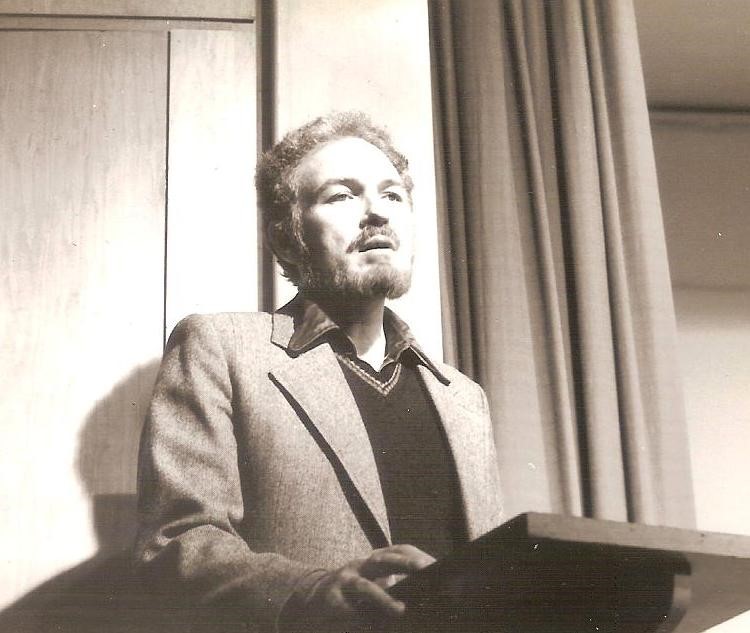

REFLECTIONS: Charles Knott, Host

Chamber for personal reflections, enough for a lifetime.

Hold to your own truth

at the center of the image

you were born with.

The Reflections column will be used now to relive and rethink a life lived in the constant search for self-realization through study and work in theater, literature, and depth psychology as well as through the many opportunities I’ve had to observe what it’s like and to puzzle over what it means to be human. On the one hand, the purpose of the column is reminiscence; on the other hand, it is to share an ongoing learning process, much like Chaucer’s Clerk, a professional student in The Canterbury Tales, of whom the author says, “And gladly would he learn and gladly teach.”

There are many thousands of men and women who have written brilliant books. We know who they are, but who are the readers? I have not been called to write brilliant books, but I like to read them. And, for me, writing is a technique for thinking about and understanding what I've read. If anyone reads what I have written and derives value from it, then I am fulfilling my vocation as a teacher, which I consider a high calling. We may have enough brilliant books; we don't have enough teachers. I am one who learns by teaching. When there is something I want to learn, I commit to teaching it and in that way learn it.

My task here is to represent the readers, to learn from the authors and to mix what I learn from them with what I already know. I write as a form of meditation and hope these meditations resonate with those who read The Grapevine.

A brief biography: Born in Atlanta, I spent my childhood in several South Georgia towns, most notably Moultrie. A perpetual student, on growing up I attended five colleges and universities and amassed graduate degrees in English, Psychology, Social Work, and finally, a doctorate from the Drama Therapy program at New York University. I was joined in this adventure by Barbara, who worked on the same degree at NYU. Back in Atlanta, when our son Jonathan was three, Barbara had taken Montessori training. Her goal was to support our education and to foster Jonathan’s pre-school learning. When we moved to Nyack, New York, she opened the Montessori Center of Nyack in a basement room of a church while I went to work as a social worker and adjunct college teacher. So close to New York, Nyack was distinctly a home for theater people, including Helen Hayes who lived just up the street from us. We had apprenticed as actors during our first college teaching stint in North Georgia. In Nyack, a theater for children grew out of the Montessori school. Barbara showed an impressive talent for writing, directing and acting, so our interests and our work began to coalesce as we cultivated our Theater for All Seasons. We soon began presenting classical pieces and participating in other theaters’ presentations as well: Shakespeare, Shaw, Noel Coward, Tennessee Williams.

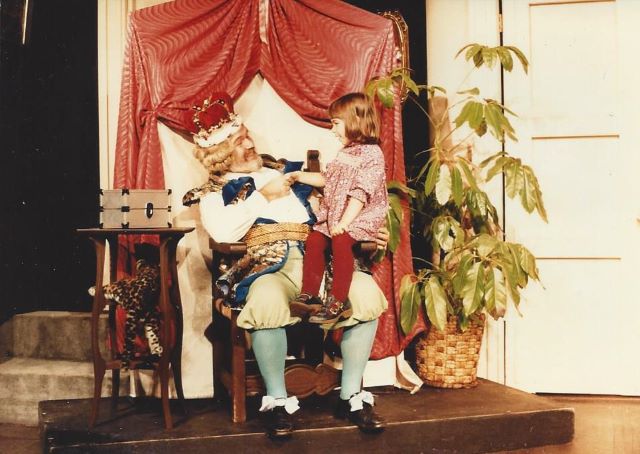

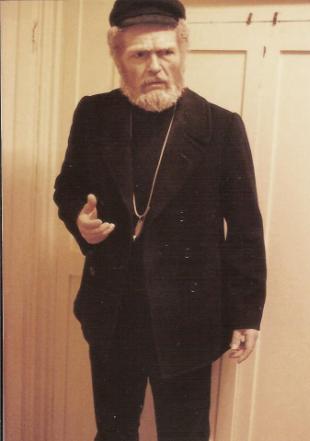

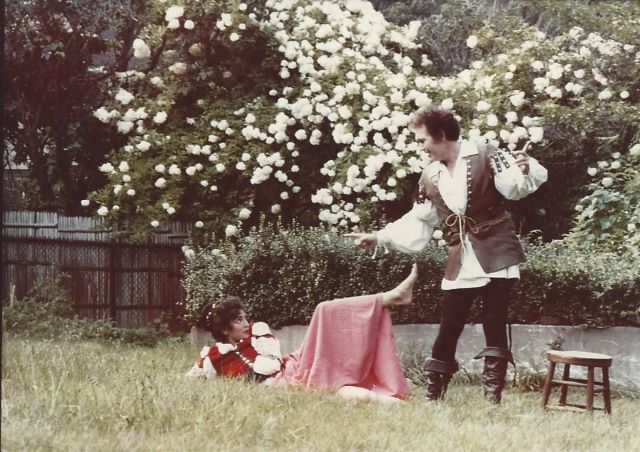

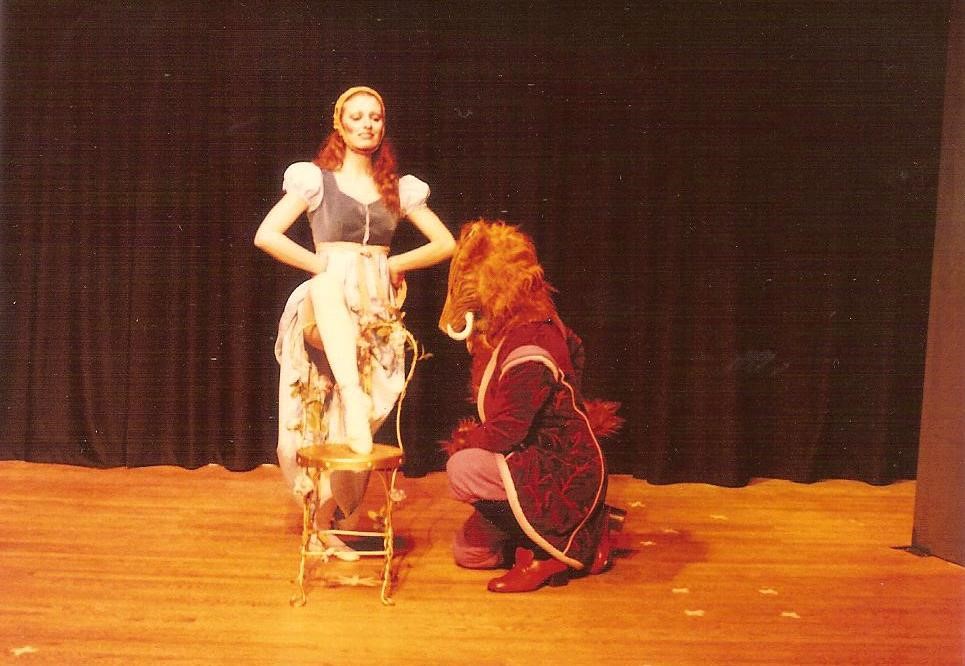

Much of this reminiscence concerns our work in theater, and I invite the reader to scroll now to the bottom of the column and enjoy a few photos taken during that time. I will discuss how theater can serve the purposes of self-realization by giving us interesting characters to absorb who then become part of our lives.

After a couple of years as a social worker in two residential treatment facilities specializing in treating extreme childhood pathology, I joined Barbara in the Montessori school where we taught young children, including our own son, based on Montessori’s principles of the prepared environment and the language readiness of toddlers. Besides running the school and our theater program, we attended acting classes at the Herbert Berghof Studio and took psychodrama classes at the New York Psychodrama Institute, both in Greenwich Village. We soon enrolled in the Ph.D. program at NYU in Educational Theater, where we pursued our specialty in Drama Therapy. I think NYU was the only graduate school in the country at the time that offered a doctoral program in Drama Therapy. We both wrote our dissertations using the psychological theories of C.G. Jung as a theoretical basis for Drama Therapy practices. Barbara wrote on Sandplay and I wrote on Mythic Enactment. After ten years we returned to Atlanta, became active in the C.G. Jung Society (serving terms as president and program coordinator) and opened a private practice in Drama Therapy which lasted for five years before we both went back into college teaching.

A devotee of the work of C.G. Jung, I read the Bollingen Edition of his Collected Works as they came off the press in the 1960s and '70s. As anyone interested in depth psychology will know, Jung's work has fostered an astounding body of secondary writing by Jungian analysts and scholars, and I have many favorites, not the least of which is James Hillman. Hillman wrote a book with a provocative title: 100 Years of Psychotherapy, and the World is Getting Worse. I like this title because it is ironic and truthful; however, it's also true that we've had a hundred years of so much else—science, for example, as well as democracy, philosophy, unending and unlimited scholarship in every field imaginable—and obviously, nothing yet has prevented the world from getting worse. I sometimes sense an element of world-saving pretentiousness in psychotherapy, and so I appreciate Hillman’s title. But, despite its implications, Hillman would agree that the deteriorating condition of the world is by no means solely the fault of psychotherapy any more than it is due to a lack of brilliant books. Perhaps it is due instead to our lack of attention to those books and to an often shallow approach to psychotherapy.

Presently, I find myself wanting to learn the meaning of aging. Hillman’s book, The Force of Character and the Lasting Life, written toward the end of his life, is enlightening to an extraordinary degree. To help myself learn new things about aging, I would like to express to readers what I am learning from reading this book. But, first of all, this caveat: the book is a continuous stream of ideas, and no summary by me will come near being a substitute for reading the book, nor is meant to be. I am writing about this book so that I can understand it and so that I can present it and recommend it to you: James Hillman, The Force of Character and the Lasting Life, (New York: Random House,1999).

The most frightening and off-putting idea that everyone associates with aging: what about death? Aging, according to Hillman, is not about death; aging is about the expansion and fulfillment of human character—a subject dear to my heart and the object of a lifelong pursuit. Death is something else, and both Hillman and I are content not to know what death really is. It would seem to be mostly a matter of going to sleep and never waking up again, ever. Aging, in contrast, occurs while you are alive and is therefore separate from death. Death can occur at any age, but the ultimate expansion and development of character requires long life and even well may be the main purpose of long life. Death is such an overwhelming idea that, to find meaning in our later years, we would do well to follow Hillman and guard against the idea of death, lest it swallow up the “new, the strange, the uncanny, the sudden, everything that belongs with the archetypal shift into unknown territory" ( p. 60). If we think of aging as nothing more than advancing along a path toward death, we make a major mistake, swallowing the meaning and defeating the purpose of advanced maturity. In short, death is about leaving—and not much else.

Hillman offers an intriguing way to think about the inevitability of the body's aging. In response to biological reductionism; i.e., that the mind, brain and even the soul are purely physiological, Hillman turns the tables by responding, "Biological systems are psychological fields, asking to be read for their intelligence" (p. 61). Hillman says that biology and psychology do not negate each other; biology is where psychology lives.

In what way and to what extent are ideas and emotions biological? To think about this question and possible answers to it, I start by considering insects. All insects live by patterns of behavior. We know that insects are not capable of rational thought; therefore, their repetitious patterns of behavior must be products of their body. Because the insect body knows and repetitiously practices behaviors typical for its species, its body reasonably can be thought of as psychological. We call this combination of knowledge and behavior "instinct," and we have no problem attributing instinct to the entire (non-human) animal world. On the other hand, we don't like to think of humans as creatures of instinct. We put an extremely high value on the human brain and its ability to make logical decisions, and we feel denigrated at the suggestion that we even possess instinct—it makes us too much like the (other) animals, a comparison we tend to resent. Even if we somehow think of ourselves as human animals, we believe we are unfettered animals, blessed with unlimited free will by virtue of our precious rational minds; we reject the thought that humans are instinctual beings—as though instinct and reason negate each other. No mingling of free will and instinct allowed!

The irony of this view is apparent when we consider that human behavior in its broad outlines is endlessly repetitious, analogous to some extent to the web spinning behavior of spiders or the colony building behavior of ants. It is not such a great leap to imagine that "culturally repetitious" or "culturally typical" behaviors are inborn in human biology. In short, I can believe that humans are creatures of instinct as well as free will. Our repetitious and instinctual behaviors, including ideas and feelings, are referred to as archetypes, and the “web” we create, speaking metaphorically, is culture.

Robin Fox (1975) makes the argument for repetitious archetypal/instinctual behavior in humans:

No human culture is known that lacks laws about property, procedures for settling disputes, rules governing courtship, marriage, and adultery, taboos relating to food and incest, rules of etiquette prescribing forms of greeting and modes of address, the manufacture of tools and weapons, cooperative labor, visiting, feasting, hospitality, gift giving, the performance of funeral rites, beliefs and the supernatural, religious rituals, the recital of myths and legends, dancing, mental illness, faith healing, dream interpretation, and so on … (as cited by Anthony Stevens, The Two Million-Year-Old Self. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1993, p. 15).

These are social behaviors that occur in all known societies, a fact that has labeled humankind as creatures who instinctively create culture. Reason and imagination are very much involved, but the guiding force underlying the collective patterns described above is instinctual.

There are those who argue that these behaviors are not inborn but are learned after birth, but all humans learn and express these cultural norms more or less instantly and automatically upon being exposed to them; therefore, humans are, at the very least, predisposed to learn them—in other words, the potential for learning these norms is inherited and readily available when the time for learning arrives. “Language readiness,” as we learned in teaching through the Montessori system, is a well-known example of a psychological predisposition that allows children of a certain age to acquire language far more quickly than any adult can acquire a language. If any person stumbles upon any of the situations described above by Fox, he or she instinctively knows the correct behavioral responses. If you happen upon a religious ritual in process, you instinctively adopt an attitude of reverence and respect, and if you are given a gift, you know to respond appreciatively. We don't really have to think about these responses because they are already in our bodies—behaviors waiting to be released by the experience of archetypal images. If learning resides in my body, then my body is a psychological field.

We know that instinct is of the body and affects behavior, and archetype is sometimes seen as the "image" of instinct. Briefly, instinct is behavior, and archetype is the image that serves to release the behavior. To give a simple and familiar example, when an adult sees a child in danger, the adult spontaneously rushes to the child's rescue. It is as if one' s apprehension and interpretation of the scene—a child in danger—is the archetypal image; the emotional response to the image triggers the instinctual, physical behavior of rescuing the child. This is a biological system of typical response to a situation that recurs endlessly throughout human history. The archetypes and the instincts are of the body. When a situation occurs that corresponds to an archetypal image, it releases physical behaviors which we are predisposed to perform. Any situation typical to human life can trigger the corresponding archetypal/instinctual response. Each situation is unique in its individual details because it is happening now to me; on the other hand, it is typical in its general outlines because it has happened countless times to countless people throughout the ages. It has happened so many times that we have taken it into our bodies, and it has become a stimulus/response event, although we do have the power to modify our responses.

Archetypes do not always lead to reflexive physical behaviors. Instead, they may produce imagery which can be read metaphorically. In The Force of Character and the Lasting Life, Hillman points out that aging, being typical of human life, causes certain archetypal systems to be activated and to flood the mind. These images, as well as the physical and mental symptoms of the aging body, have meanings beyond aches and pains and the absence of youthful strength and stamina. Understanding these images and symptoms metaphorically leads to character development. To give an example, let's say you can no longer climb stairs with youthful ease. Rather than despairing about physical changes, you might think psychologically and ask in what sense am I still climbing—and why? What psychological summit am I attempting to reach? Considering my age, am I using an outdated strategy? Such trains of thought may lead us into mature understanding. Hillman reminds us that body metaphors continue to be legion as we age. The aging body is not meaningless protoplasm waiting to die; its symptoms are changing, and its physiology is asking to be read as psychology, not so that we can die but so that we can fulfill the meaning of our lives.

In his visits to the Pueblo Indians in New Mexico, Jung was told by an Indian elder that the white man is crazy, "because he thinks with his head!" When asked what he thought with, the elder touched his chest, indicating that he thinks with his heart. For him, the heart is superior to the brain. In some cultures the liver is considered to be the center of consciousness. Regarding the intelligence of the body, I have recently been reading that the human digestive system is now being seen as an extension of the brain. We know that we all have "gut feelings" and "gut reactions” which we sometimes prize above intellectual insights. The gut is sometimes smarter than the brain.

Joseph Campbell referred to dreams many times as "the energies of the body organs." Hillman says, "… a body is a form, a psychic field, a house of souls who make their homes in all its rooms. As a psychic field, the physical body is a citadel of metaphors that can be read for psychological intelligence as well as for bio-information" (The Force of Character, p. 59). And he suggests that we need a proper vocabulary to transform thought from physiology to psychology, using words associated with character: "honor," "dignity," "authority," "prudence," "grace," "depth," "mercy," "courage," "constancy," "loyalty." He likes "understanding," "necessity," "soul," "philosophy," "intelligence," "insight," "vision," "idiosyncrasy," "passion," "folly," and so on. Such terminology suggests that familiarity with the humanities is useful in our study of character.

I have felt a number of subtle changes in my own psychology as the years have gone by, and come to think of it, they are bodily changes. For example, I used to love acting in plays—my body liked to be used by a script and to modify itself to serve enactment; but I no longer want to be on the stage, and I no longer want to use my body to become a character invented by a playwright. My brain is too full of its own imagery to memorize hundreds of lines. I have no space now for the playwright's lines or for the stresses that accompany the acting process. I'm quite content to sit in the audience. Once upon a time, I was consumed with a "performance hunger"; now I am content to let younger people entertain me. And I don't envy them. They are no threat to my own aging character. I admire them and praise them to others. In the past I would jealously ache for an opportunity to trade places with them, but no more. My mind and body have other interests.

“Reading subjectively,” as I am now advocating, does have a corollary to acting. As an actor, one links one's inner self to the role. The use of self in acting is famously known as "the method." You take the role into your body, into your "muscle memory." For the time of the performance, your body belongs to the character you are enacting. Welcoming a new character to take over your body always changes you; aspects of that character stay in your body permanently, and your character expands to accommodate them. I have played the silly king in The Emperor's New Clothes, the suave Englishman in Private Lives, an 88-year-old sea captain in Heartbreak House, a Catholic priest torn by his sexual love for a young nun in The Runner Stumbles, D.H. Lawrence in our Portrait of D. H. Lawrence that ends with Tennessee Williams' I Rise in Flame Cried the Phoenix, the Beast (and Prince) in Beauty and the Beast, as well as Shakespeare’s Petruchio, Falstaff, Oberon, and others. In every case, I found myself in the characters, and they, as autonomous entities, found themselves in me. Together we worked lovingly to fulfill the intentions of the playwright and to entertain the audience. But, when the show had run its course and closed, the characters stayed with me and blended into my own being. I walk, talk, feel, think—in short, live— differently from having welcomed these lively fictional characters into my body.

While I used to strive to be a method actor, I am now a "method reader" instead. As I read, I take the text into my own “citadel of metaphors.” This citadel has expanded over time, and re-reading a few of the many, many books I have read previously creates that delightful experience of reading them again as if for the first time.

In my 20s, I worked on a Master’s Degree in English and American literature with great relish, but with an often superficial understanding. I possessed only so much that I could bring to the reading. When I re-read those same pieces today, I bring intervening decades of my own metaphors to interact with the masterpieces of the printed page. I am reminded of Mark Twain's famous ironic remark about discovering, on returning after his own lengthy absence from home, how much his father had learned! I am amazed at how much the great authors have learned since I read them in the 1960s. Nowadays, they seem much more brilliant, visionary, and exquisitely aware. Obviously, it is I who have changed, not the books.

Another paradox: in maturity, when revisiting physical sites of one's childhood, those sites often seem to have shrunk in size and general impressiveness. In contrast, when we leave behind the callousness of youth and revisit in old age what Yeats refers to as "monuments of unageing intellect" (from Sailing to Byzantium), those monuments seem far grander. When I revisit my ninth grade playground, I'm astonished at how small it is in comparison to my memory of it. But, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner that I read in the ninth grade is by no means The Rime of the Ancient Mariner that I read today. Coleridge has grown impressively wiser in the intervening years, and while the actual playground of my youth has shrunk, the Rime has expanded in grandeur.

Today, my delight is that I have many metaphors of my own that I can mingle with those of the great authors as I read their work, a delight not available to me in my youth, but which now has become a profoundly meaningful reason for embracing a lasting life. Surely, reading is one reason life keeps us around so long! Let the 20-somethings and 30-somethings propagate the race and bring children safely from birth to adulthood. We older folk must tend to our metaphors and use them to build character—and, when we can, as in the present case, to amuse and entertain you, Gentle Reader.

Copyright 2019, Barbara Knott. All Rights Reserved.