The Grapevine Art & Soul Salon

Entertaining Ideas: Charles Knott

Things that Go Bump in My Mind

One of our goals at The Grapevine is to start conversations and encourage readers to carry them forward, inwardly as well as outwardly with others. At a recent meeting of the C. G. Jung Society of Atlanta, I heard a lecture by the distinguished psychoanalyst, professor and author James Hollis who wrote Hauntings: Dispelling the Ghosts Who Run Our Lives. He discussed his book, and I have since read it with great interest and pleasure. It addresses questions that have been with me much of my life and continue to haunt me. I'd like to repeat some of his questions here and respond to them.

In Hollis' presentation, "hauntings" are those ideas, compulsions, obsessions and complexes that rule our present lives as if they were ghosts who overpower our conscious intentions. This is of interest to me because I often wonder how sometimes I set out to do one thing and end up doing another; mean to say one thing and say something else; feel justified now in doing a thing and later feel foolish for having done it; set out apparently obeying and pleasing my soul and later feeling like a fool. (Am I talking only about myself, or has this also happened to the reader?)

One of my hauntings is entrenched in a parental complex. Let me give you a few images of it.

Yesterday I cut the grass on the four-acre lawn in front of the family home I inherited when my parents died. Predictably, as I sat down on the riding lawnmower and got it moving, my father's "ghost" appeared in my imagination and started criticizing me. He noted that I do not run the lawnmower as hard now as I used to; is this because, now that I somewhat more mature, I am becoming wise like him? In real life, he teamed up with the next-door neighbor to watch me cut our lawn. Their commentary was pretty much continuous and entirely disapproving: I ran the lawnmower too fast and too hard, and this caused it to break down in the short run and wear out prematurely in the long run. My father, as if it were a moral duty, tirelessly reported these observations to me, trying in a sincere fashion to be helpful. I wouldn't listen because I was impatient to get the job over with and, frankly, I didn't respect his opinion.

You see, for 10 years I was not present to cut the grass, and my father allowed hedgebush to grow 15 feet tall in the front yard. The growth was so thick that people secretly camped out there at night next to the pond. They left behind empty whiskey bottles and ground scarred by campfires. Because of the thick growth, none of this was visible from the front porch. Eventually, after returning from New York and living with my parents for a year until we could establish our own household, my wife and I hired a contractor with a front end loader and a dump truck to uproot and cart this wild growth away so we could plant grass.

In a matter of weeks, there was radical improvement in the appearance of the yard, but instead of marveling over this transformation, my father chose to remember that, through the years, he had regularly cut the grass and that he did it correctly. To him, it was as though that beautiful lawn had always been there and had always been immaculately tended by him. I, on the other hand, was incompetent and uneducable when it came to cutting the new lawn he had watched us plant. He saw me as a very serious problem, and I made him awfully exasperated. This is the drama that replays in my mind each time I cut the yard. It is as annoying as it is inevitable and irrepressible.

Hollis says that for some of his patients "father offers sustaining support, guidance, and empowerment, while for others father is a monster who eats his children out of his own anger, insecurity, and infantile jealousies." My father would tend to be one of those "others." Hollis also says, "Fathers can hardly fulfill their archetypal role if they themselves have not been fathered. How can a man pass on to his children what he has not himself been given?"

Those passages definitely describe my father. He was badly fathered, and he failed to "re-parent himself." In this way, he passed the problem along to me, and I am still struggling with it. In the spirit of turn about is fair play, here is a passage from Hollis that describes me: "So, we transform our colleges into holding tanks for confused adolescents, swimming in the arms of alma mater, looking desperately for the empowering father who might authorize their lives and validate their journeys, their curiosities, their individuation necessities." As a confused adolescent, I swam long and hard in the arms of alma mater, alternating as student and teacher, amassing three Master's Degrees and a PhD. Apparently, a father like mine produces the need for quite a lot of validation.

After having been delivered certain crushing messages by the parent, Hollis asks, "What else is one to do with one's life ... but become a psychologist, or an accountant?" Got me again! For me, accounting was definitely out, but, along the way I did also become a pretty good Jungian scholar and one of my master's degrees is in psychology and another one is in clinical social work. After writing a Ph.D. dissertation on mythic enactment as a drama therapy technique, I did a seven-year interval as a psychotherapist. Then, I again returned to swim in the arms of alma mater, this time to continue a career in teaching.

And now, while thinking about these dynamics, I'm understanding a recent dream image: I am again 15 years old and I am filling the tank of my motor scooter at the Spur station on the corner of 5th Avenue and Main Street in Moultrie, Georgia. Why a Spur station? That company has been out of business for years. But we know from experience that dreams often speak in metaphors. Who or what was the spur that the dream wanted to bring to my attention? I believe that my relentless conflict with my father always had within it, as its creative core, a spur that drove me on my spiritual and intellectual journey, my individuation quest. In a sense, the conflict has been my most valuable possession.

One picture of my father complex, or "ghost," as Hollis would have it, is a very active and aggressive image that appears often in my mind. But my "father ghost" was also seen by someone else from another point of view: A guest staying in my house reported recently that she had seen a phantasm in the den. It was in the shape of a little old white-haired man who was wearing only boxer shorts and a sleeveless undershirt. He positioned his thumbs on either side of his head, waved his fingers and stuck out his tongue at her. This is a pretty precise description of my father. He dressed like that around the house, and he liked to give people "the razberry."

So there are two types of hauntings: internalized figures, based on memory and often referred to as "complexes," and external phantasms which might actually have physical reality. I know for a fact that haunting figures have a psychological reality. Yet, when I hear this accurate account of my dead father's manifestation before the eyes of someone who never knew him, I am inclined to think that ghosts also may have a physical reality.

To me, ghosts are far more interesting and important on the psychological level than on the physical level. Hollis reminds us that Jung greatly respected the influence of spiritual beings on the development of personality and in shaping of the destiny of the individual. Also, as Roderick Maine has recently written in Jung on Synchronicity and the Paranormal, Jung often, and over the course of many years, went beyond the traditionally spiritual and entered the spiritualistic, attending seances and formulating a sophisticated theory of synchronicity - that is, coincidences that seem to be organized by meaning rather than cause-and-effect. Are synchronicities to be seen as ghosts at work?

Complexes, of course, are so fundamental to Jungian thought that he originally intended to call his psychology "complex psychology." And Jung famously defined God as "all things which cross my willful path violently and recklessly, all things which upset my subjective views, plans and intentions and change the course of my life for better or worse." By this definition, complexes are included with those things he calls God. Does that mean that my father's ghost is a manifestation of God?

As a child growing up in the Episcopal Church, I was often "haunted" by the "Holy Ghost" of the Trinity. I never knew the difference between the Holy Ghost and the Holy Spirit. Sometimes the terms are used interchangeably, and I gather these are not always forces for good. Like Puck in A Midsummer Night's Dream, the Holy Ghost/Spirit might well go "misleading night wanderers [and] laughing at their harm." After all, Jesus himself taught us to plead with God to "lead us not into temptation. . . ." One way I like to paraphrase that prayer is "Please, Dear Lord, don't make a fool of me again today like you did yesterday."

Dr. Hollis makes suggestions about working with the ghostly figures in one's life, such as bringing them to consciousness, watching them behave in dreams and fantasies, interacting with them through exercises in active imagination, and deciding when to confront and dispel them and when to learn from them. What I have learned from my father is how vulnerable we are to complexes, how difficult it is to "get outside" them and have an objective look, and also, more recently and more generously, how to appreciate their creative component. They can be spurs to achievement or, to change the metaphor, grains of sand to be turned into pearls.

A lifetime spent at such work needs good support and guidance, and I appreciate what James Hollis has given us.

More Conversation Starters

The following italicized questions are based on notes I took from Prof. Hollis' lecture. The comments on these questions are my own.

Hollis asks, What am I apart from my history? I often tried to shed my own history and find my authentic self in theater. There, I could substitute the history of the character I was playing for my own history, but there is a moment when you are working at acquiring a character and you feel you have no character at all and no history. So, through theater I was sometimes able momentarily to stand outside the history both of myself and of the character I was playing. It was an empty feeling, but it gave birth to spontaneity which, in turn, enabled me to greet myself with surprises from aspects of my own character that I was unaware of. I stood outside my own history for a few moments, and then observed the void being filled.

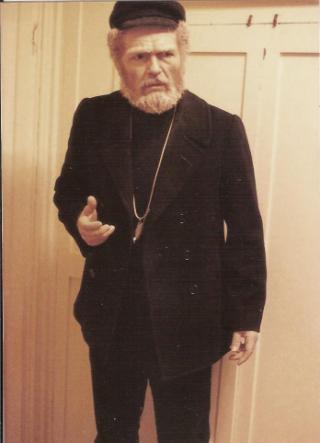

Acting also had the therapeutic effect of calming the complexes. My complexes seemed intimidated by stage fright, and they got out of the way because they respected the urgent importance of performance. Miraculously, they would also "audition" for performance during rehearsal. "That's something I would say," and an imago would raise its hand and ask for a part. If it worked, I would use it. I used my father imago extensively in a production of Heartbreak House, where I played Captain Shotover, an 80 year old retired sea captain. Complexes love theater!

Hollis refers to "remembering the future," by which he refers to our memories of what our plans for the future used to be. And he reminds us, with Faulkner, that the past is never past. On hearing this, the first thing that came to my mind was the way Al Gore introduces himself to his audience in a presentation of An Inconvenient Truth: "I used to be the next president of the United States." What a future he's remembering!

I remember many of my future plans. The pursuit of all of them, and the eventual abandonment of many of them, made up the substance of much of my life. I am remembering now that one of my future goals was to find the leisure to write back and forth in an endless conversation with Barbara, which, to my great surprise, I'm now doing in this public forum where we write, discuss, and eventually publish some results of our conversation. I'm remembering the future even as it unfolds in the present.

Hollis asks: What is trying to enter the world through me? I can feel an open portal through which information flows when I write and teach. Something tells me what to say, analogous to the way that lines previously memorized would come to me when I was acting in a play. This would seem to be latent knowledge already possessed by me without my consciously thinking about it. An autonomous force is entering the world through me. Is this my purpose in life?

Hollis used the phrase "swamplands of the soul." This phrase doesn't bother me now the way it would have when I was young. Back then I often felt like I was swimming in quicksand, or immersed in a complex and unable to fight clear of it, and I would feel states of extreme anxiety. Now, not so much.

Hollis says we need to examine and transcend the sources of our sense of betrayal, shame and guilt. Even though I have been extremely fortunate when I compare my lot to that of billions of people on this earth, I still sometimes feel that I was betrayed by life. Why wasn't I the son of Socrates with a mother that resembled Shakespeare's Portia? (Of course, they may not have got along well as a couple.) I also wonder why I haven't inherited billions of dollars so I could influence the well-being of the world in wonderful ways. (I'm sure I could make it a much better place.) Oddly, I am now remembering reading that Adolf Hitler shared a similar fantasy. He was furious at fate for not allowing him to win the lottery. I don't always like the company my fantasies keep.

Hollis asks, What is your core complex? I hope my core complex is made up of compassion, kindness, intellectual curiosity, and good will toward the world. All shine and no shadow! What my core complex actually is, I don't know. And, in fact, I just realized I'm describing traits, not complexes. It would seem that I'm evading the question of my core complex.

Hollis asks, What contract do we imagine we are operating under? Suppose we find there is no contract? Jung's Answer to Job gives a profound and extensive inquiry into this question. Job assumed that if he played by God's rules he would be rewarded with good things. He believed that was the contract he and God were working under. God seemed either unaware of or disinterested in any contract with Job, and rather flippantly and unreflectively entered into a new contract with Satan. He contracted to torture Job until Job cursed him! Job courageously worked through his bewilderment at the apparently purposeless and cruel suffering God inflicted on him and eventually stood beside God and looked at the world through God's eyes. Did they exchange perspectives? Jung implies that Job "educated" God about the nature of human suffering and that God comes back as part-human Jesus so that he can fully comprehend that suffering. Jesus is God's "answer to Job." Quite an examination of a contract.

Jung later said he regretted referring to "God" in this essay and that instead he should have referred to the "God imago," defined as an imagistic repository of human impressions of God. So, when I talk about the image of my father appearing externally to a house guest, and as an imaginary figure inside my head, I should probably refer to my father imago instead of to my father. Perhaps that is another way of naming the father complex.

I'm interested in yet another twist to the meaning of ghosts in our lives. Suppose we are here to further their individuation. Just as Job wrestled with God so that God could feel empathy with human suffering, I feel that I am wrestling with my father because he is trying to learn something from me, even though he's been dead for more than 20 years.

Judging from the way he approaches me in my imagination, his ghost is still trying to educate me, or is "spurring" me to find my education wherever I can. But the question is, what contract do we imagine we are operating under? My father "contracted" to raise me and prepare me to live in the world. Apparently, I have contracted to wrestle with him - as man and as imago - and to finish his unfinished business. Maybe he secretly wanted to be a student/psychotherapist/actor/teacher and, lacking the means to do that, elected me for the job.

The conflict did spur me through graduate school and years of training in psychotherapy, with its attendant soul searching. Maybe the old man's ghost is paying his way with me after all. I wonder if I am doing him any good.

And what if I find there is no contract? I don't think it would make much difference. I think the struggle would go on for all of us. But what if it didn't? What effect would that have on our psychological development? Does our struggle help the ghosts as well as helping us? Is there an afterlife, and do we become ghosts when we die and then bedevil the living? Are we already ghosts (complexes) in the minds of those who know us? A wonderful book has been written on this topic: Greeting the Angels : An Imaginal View of the Mourning Process, by Greg Mogenson.

Hollis says, provocatively, "What you have become is now your greatest obstacle." This is a particularly enigmatic concept. To quote from Hauntings, "We do not rise in the morning, look in the mirror while brushing our teeth, and say to ourselves, Today I will do the same stupid things, the reflexive things, the aggressive things which I've been doing for years! But more often than not we indeed do the same stupid, reflexive, regressive things. Why?"

Hollis says one of our hauntings is our own unlived life and the unlived lives of others. Some of the relevant questions here would include, How many things have I and everyone else done that we should not have done, and how many things have we left undone that we should have done? What burdens am I leaving for others that I should be tending to myself? And how do these things control my ideas, obsessions, compulsions, motivations and unconscious agendas? For how many people am I working, living out their unlived lives, and how many are working for me, living out my unlived life? Where does my authentic self fit into this, and to what extent will I ever discover it?

These are all questions that haunt me.

Thank you, Dr. Hollis, for a delightful and instructive evening!

REFERENCES

James Hollis, Hauntings: Dispelling the Ghosts Who Run Our Lives. Asheville, N.C.: Chiron Publications, 2013.

Greg Mogenson, Greeting the Angels : An Imaginal View of the Mourning Process. Amityville, N. Y.: Baywood Publishing Company, Inc., 1992.

Copyright 2015, Barbara Knott. All Rights Reserved.