The Grapevine Art & Soul Salon

Views and Reviews

Barbara Knott: Jeff Fields and Terry Kay at the Georgia Center for the Book

Jonathan and I traveled to the Decatur Library on Monday evening, June ll, to attend an author event sponsored by the Georgia Center for the Book. We became stalled in the parking lot under a sky that was cracking lightning and whirling tree tops and whipping rain sideways as if Zeus had decided on this night to mock those who think a myth is a lie or that fiction is the opposite of truth. So we waited, filled with awe at the outburst of weather, Jonathan for once reduced to a single-word response, uttered with eyes open wide and voice low: “Damn!”

Suddenly the rain stopped and inside we found Nancy Law practicing what any retired librarian like her would know to do in untoward weather: arrive before the storm starts and settle down with a good book. The three of us moved on to the auditorium where a crowd of fifty to a hundred gradually gathered to enjoy the show.

The occasion was a discussion onstage about writing that featured Georgia novelists Terry Kay and Jeff Fields together with Bill Starr, Director of the Center. Both guests have debut coming-of-age novels that were first published in the l970s and reissued recently by the University of Georgia Press: Terry Kay’s The Year the Lights Came On (1976) and Jeff Fields’ A Cry of Angels (1974).

Kay and Fields were born in l938, making them one year shy of entering their eighth decade, a fact that might set a sedate tone if both men, carrying a wealth of years to enrich their personal charm, weren’t so lively and attractive. Terry Kay, white hair and beard, often wears a beret that gives him a dapper persona. Jeff Fields is tall and slender and youthful looking.

And Bill Starr was very much at home as host of the event, one of many he arranges in a given month. Turns out the three had appeared together once before, at the Georgia Literary Festival in Elberton in 2005. So they were already warmed up to perform, and the evening was filled with laughter and congeniality, both onstage and in the audience.

Elberton, Georgia, is a central location for the two writers, being the fictional Quarrytown of Jeff Fields’ novel and the place where he grew up. Terry Kay comes from Hart County and spent his youth in Royston, Georgia, near Elberton. The two did not meet until after their first books were published, when they were introduced by a mutual friend, Atlanta playwright Cary Bynum, whom both had known at the University of Georgia. According to Kay, he and Bynum once appeared together in a production of Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie, with Bynum as the Gentleman Caller and Kay as Tom. Terry Kay followed his interest in theater to become an Atlanta film and theater critic before he turned to writing fiction. He now lives in Athens, Georgia.

Jeff Fields’ first vocational yearning was to become an actor. He, too, studied theater at the University of Georgia before going to UNC at Chapel Hill. Jeff Fields began writing while still in college at the University of North Carolina, then worked in television as a producer and host, first in Greenville, S. C. and later in Jacksonville, Florida. He lives in Atlanta now.

Bill Starr asked a few questions to get the discussion going and elicited these responses among others:

TK: I’ve never been afraid of writing. It was never a fearful thing to do. It was just a thing to do.

JF: I write with a great deal of fear. It’s an agony and ecstasy experience all the way.

TK (on influences): Zane Grey, Erskine Caldwell’s The Sacrilege of Alan Kent. Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Thomas Wolfe, John Steinbeck (“the best in the country”), Flannery O’Connor.

JF: Mark Twain, Mark Twain, Mark Twain. John Steinbeck. Harper Lee.

TK: I don’t ever know where a book is going when I start. It is the joy of discovery….

JF: I started [A Cry of Angels] with an image of freedom, boys on inner tubes floating down a river, and one thing led to another….

TK (on Jeff Fields): The writing is brilliantly done. For me, it’s pure theater. The characters are the kind you would find in a classic play.

JF (on Terry Kay): He is a passionate writer, a born storyteller. And talk about theater! Shadow Song is theater.

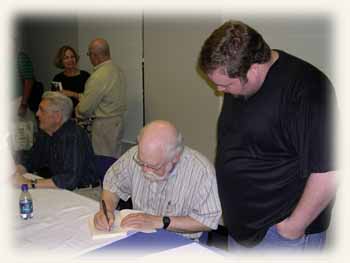

The above randomly quoted comments don’t begin to suggest the badinage that flowed so easily between the two writers and entertained the crowd of booklovers. Some of that emerged from Fields’ telling that his book now contains a foreword by Terry Kay and how Amazon.com had listed it as authored by Jeff Fields and Terry Kay and how he and his publisher agreed that the listing was certainly misleading, but it might help sell some books. That theme got picked up several times and during the booksigning afterwards, Kay was heard to say, “I get such a kick out of signing Jeff’s book.” And there he was, writing his signature across the title page over Foreword by Terry Kay.

A big laugh erupted when Kay mentioned that his book title, The Valley of Light, was not his choice. “It sounds to me like the name of a Thomas Kincaid print,” he said. A discussion of varying book lengths drew another round of appreciative laughter when Kay told how Pat Conroy said he had submitted 2100 pages of manuscript for Beach Music and complained, “They want me to take 600 pages out.” Kay said he responded that if he were to remove 600 pages from one of his own manuscripts, he would owe the publisher 400 pages.

Bill Starr became particularly animated during a discussion of the Internet’s effect on the public’s reading habits. He upheld the primacy of the book as a physical object and praised regional publishers and university presses for their role in keeping books alive. The reissue of the books by Kay and Fields is an example.

Fields prompted Kay to tell a story about one experience with Hollywood when he was engaged by Warner Brothers to do the screenplay for Shadow Song. Studio representatives were stunned by his work, Kay said, which shouldn’t have been so surprising, he thought, considering that he had been in the movie review business for years. Then they said to Kay, “We’d just like to tweak it.” Three tweakings later, Kay said, his protest elicited this response from the movie makers to the author: “You don’t understand the book.”

A man in the audience spoke up, “I’d like to compliment you, Jeff.” He then told how he had written to Fields from the Midwest when A Cry of Angels was first published and how Fields had written a two-page letter back to him. Fields laughed and said, “I’m glad that meant something to you. I wrote to a lot of people out of gratitude for their liking my book.”

Another audience member asked Fields how he had come up with the term “brass cracker” used in A Cry of Angels to describe Gwen Burns, the Atlanta socialite who comes to Quarrytown to marry Jayell Crooms. Fields replied that Elberton had been visited by young women from Atlanta carrying some sophistication that “they really wanted us to know about.” It was a way of finding equilibrium to suggest that underneath the little bit of polish they wore, they were rooted in the same poor white rural South as those they liked to look down on.

Fields is less well known than Kay, though he has a dedicated following based on the one book, while Kay, of course, has had a string of successes including To Dance with the White Dog and Taking Lottie Home. He was inducted into the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame, alongside Jimmy Carter and Frank Yerby, in 2006. Yerby was in his prime while I was growing up in the l950’s, eagerly reading one bodice ripper after another even as I was memorizing “Yon Cassius has a lean and hungry look….” No information filtered down to us that Yerby was from Georgia or that he was a man of color. The trio suggests how varied Georgia writing can be.

One reason Terry Kay made the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame may be his extraordinary ability to elude being typed. His books are all different. And his fame is not only local: his books have sold over two million copies in Japan, he said. Kay quickly explained to those bugeyed with awe over the money he must be making that he gets only eight cents a copy. Still, if my math is right, that amounts to $160,000 for his 401K. When asked what he values about Hollywood, that was his answer: 401K.

A lively discussion of “sanity and the publishing industry” led to Kay’s pointing out that a number of writers from Atlanta have been successful because they found a genre. When Fields wondered if A Cry of Angels would be published today, Kay responded, “Yes, it would. There are some books that just will be published….”

One is tempted to say--and I will say it here--that Fields’ novel effectively stakes out a claim in the territory pioneered by Mark Twain and called by subsequent readers the terrain of the “great American novel.” The social conflicts in his book are serious and dramatic. They involve class struggles and racial undertones simmering during the l950s; they also include the ill effects of progress on a local grocery store, the fate of Native Americans, the role of creativity in community life, and the plight of an aging population. The thematic search for personal freedom and comradeship is thoroughly American, as is the capacity for finding humor in unsettling situations. Whether Fields comes closer to Mark Twain or to Harper Lee or John Steinbeck matters less than that he stands among them with a similar eye toward what is and always has been important in American life: how to find freedom to unfold the full potential of the individual and at the same time to cultivate a creative community able to support multiple points of view.

Eventually, Fields was asked what he referred to as the “inevitable” question, What has been going on since you published A Cry of Angels in 1974? In other words, why only one book? He said that he had written a second novel as well as some stories, but that he had not been able to get the book published. He said he spent five years writing the second book and three years waiting by phone and mail delivery for his manuscript to make the rounds of the twelve editors who looked at it. Then he quit writing for a time. “I couldn’t touch a typewriter for two years,” he said.

The above expression of exasperation gave rise to comments overheard later at the booksellers’ table where one woman said to another: “Poor thing. Made me want to send him a casserole or something.” For a moment I felt as if I were in a Jeff Fields or Terry Kay novel. That sense of having one foot in fact and the other in fiction was not diminished by the appearance of Cliff Graubart, onetime owner of the Old New York Book Shop on Juniper Street and still a purveyor of antiquarian books, who was walking around talking to Pat Conroy on his cell phone and conveying greetings among the three writers. Nancy and I watched as a middle-aged blonde woman strode up to Graubart and said, “My mama once tried to arrange for you and me to go on a date.” She gave him a hug, cellphone and all. He swung around to watch her walk away and said, “Who was that woman?”

Jeff Fields does have another novel in progress. He acknowledged from the stage receiving helpful comments from his fiance Linda Sherbert, a magazine editor and theater artist who also happens to be Jonathan's playwriting instructor. He has recently written a play, now under consideration for production in the Metro Atlanta area. And A Cry of Angels presently has a movie option on it.

The audience had all been given tickets on the way in for a drawing that took place at the end of the discussion; the prize was an advanced reading copy of Terry Kay's The Valley of Light: Jeff Fields drew out of the basket the number 619091. I had 92 and Nancy had 93. We both looked at Jonathan who was grinning. Terry Kay signed it, For Jonathan-a lover of words—Thank God!

And I remembered what it is that I like about Terry Kay’s stories: he isn’t afraid to explore the extreme effects of love on the human soul, as he did in To Dance with the White Dog. Someone I love once gave me a story that impressed me very much, an obscure piece noticed in a newspaper and passed along as if it were important: a man whose wife died carefully packed her ashes into capsules and consumed them, one or two a day, for as long as they lasted. In Kay’s novel, the appearance of the white dog to Sam Peek after his wife Cora’s death has about it the same sense that love can transcend all boundaries.

We all have many lives to live in books, and the Georgia Center for the Book plays a valuable role in the cultural well being of Atlanta, not only by celebrating books but also by elaborating our experience of reading in bringing to us a succession of writers with whom we can have conversations.

And Zeus just might be dancing with delight rather than mockery around such an occasion.

You can read Jonathan’s review of A Cry of Angels by going to Presentations and clicking on the link under his name. There are pictures from the booksigning at Palmetto with Jeff Fields in October 2006 under Archives, Winter 2007, Miscellany.