The Grapevine Art & Soul Salon

Views and Reviews: Barbara Knott

MUSING ON EQUUS Spring 2013

Actor's Express artistic director Freddie Ashley made the choice to include Peter Shaffer's Equus as part of the theater's 25th anniversary season, and in doing so, astonished himself, as he recounts in the program notes. The suggestion by Production Manager Phil Male came like a thunderbolt, he says, reminding him that the play is "at once visceral and cerebral, spiritual and earthy," and that it is "a play of massive thematic and emotional bearing."

The play was first performed in the l970s and is considered by many critics since then to be dated, a flash-point for one decade and then done. But I found this re-introduction of the play to be even more timely now than it was then, and I am glad neither Mr. Ashley nor director David Crowe failed to see its import for our time as well. I don't know what it was that convinced them, but in my case, it's the reading and thinking I've done this year about the continued diminishment of what it means to be human, by our turning so far away from nature to technology that, as the world becomes more and more virtual, we humans are losing our footing, our place, our standing among the creatures of the earth and, below all, our sense of wholeness and of the holy. Something in that dilemma is at the heart of this play: not the technology as such, but the loss of what might be called the instinct for worship developed in our species over aeons of being in the world of nature and imagining it as alive and sacred.

Shaffer's theme is akin to something psychiatrist Carl Jung expressed in a 1952 interview with Mircea Eliade: The modern world is desacralized; that is why it is in a crisis. The modern person must rediscover a deeper source of his own spiritual life.

Martin Dysart is a psychiatrist who confronts his own moral complexity as he treats a l7-year-old boy named Alan Strang, recently placed in the psychiatric hospital for the crime of having blinded six horses with a steel spike. Dysart is able to break through the boy's defensive insistence on speaking through television advertising jingles by placing himself on an equal footing with the boy when he suggests a game in which they ask each other questions, with the stipulation that each will give honest answers.

Gradually, we move with Dysart into the mystery of the boy's act, which has religious overtones and sexual undertones, both emanating from the thematic loss of appreciation for the sacred and the holy as it is embodied in natural life. Dysart elicits from Alan Strang images of his sexual attraction to horses, one of which, Nugget, has been the nightly companion of the naked, bareback boy rider for whom the horse's eyes are the eyes of God. The boy has turned away from the Christian world, so problematically represented by his mother's religious fanaticism, and from his father's atheism, an equally inadequate world view, to the pagan world where horses move between their kinship with humans (as centaurs) and their kinship with the gods (as Pegasus, for example). His "crime," which is really an act of spiritual confusion, comes when the girl succeeds in seducing him and evokes the disapproval of the horse-god in his head. Imagining that the horses in the stable "see" him too clearly, he is moved in a panic to put out their eyes.

Having seen with his healer's eyes into the mystery, Dysart still is faced with whether his treatment of the boy will at best return him to the dreary order of the normal, filled with ennui and sadness from a vague sense that life is going unlived. Having acknowledged this missing piece of modern life, the capacity for worship, where will Dysart find the deeper source of his own spiritual life? And where will Actor's Express find the actor who can take on the role of this Everyman who has the moral complexity of a Shakesperean figure struggling to become fully human?

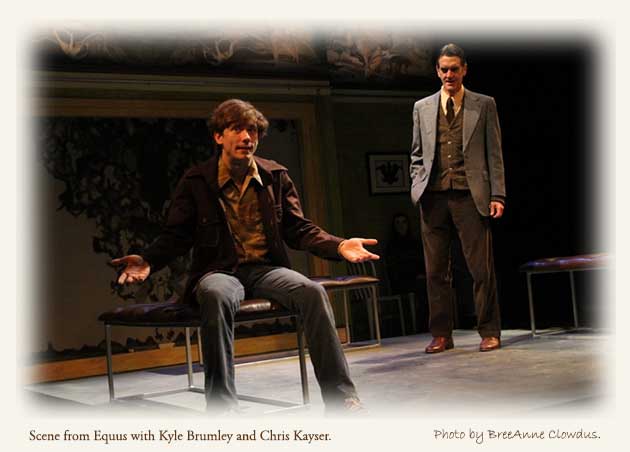

The actor chosen to play Martin Dysart was Chris Kayser, whose capacity for such complexity I have described elsewhere as being illumined by the statement of Roman Terence, I am a human being. Nothing human is alien to me. That maturity makes Kayser the perfect actor to embody Dysart and through him, to carry the play. His brilliant performance was well balanced by Kyle Brumley's as Alan Strang, whose apparent craziness is gradually revealed as a world-shattering, passionate plunge toward that deeper source that seems through his radical yearning to be found in the more-than-human world, specifically in nature and all the bodies of nature, including our own.

Sarah Elizabeth Wallis, as Jill Mason, the girl, is exactly right. Watching boy and girl on stage naked, one thinks of the courage of these budding actors following in the barenaked steps of Chris Kayser who, in Quills, played the Marquis de Sade in full nudity for the entire play. Shameless! I mean that as a tribute.

The entire cast performed with the strength needed to carry this dense and intense play: Rial Ellsworth and Joanna Daniel as the boy's parents, Kathleen Wattis as the colleague who thinks Dysart is the only one who can treat Strang, Rachel Shuey as the nurse, Eric Brooks as Harry Dalton, owner of the stables. The ensemble of horses played by Christina Boland, Matthew Busch, Niki Edwards, Jordan Hale, Bryn Striepe, and above all, Nugget, whose role was played by Jason-Jamal Ligon, provided an uncanny beauty and palpable reality to the horse-god image proffered by the play.

Displaying all these forces together on one stage was the impressive work of scenic and costume designers Isabel A. and Moriah Curley-Clay, together with lighting designer Mary Parker, sound designer Joseph P. Monaghan III, and stage manager Charlie Moore. Cheers for them and especially for Director David Crowe who brought this production into its full potential. And thanks again to Freddie Ashley for listening and responding with that Yay!

Copyright 2014, Barbara Knott. All Rights Reserved.